After a four-year hiatus, Argentina resumed her predilection for socialist governments by swearing Alberto Fernández into office in December 2019. Like many Argentine presidents before him, he faces the huge challenge of steering the Argentine economy out of a self-inflicted crisis.

Mauricio Macri, the outgoing conservative president, failed to live up to his promise of poverty reduction and liberalization. Rather than tackling the root causes head on, he adopted a gradualist approach leaving untouched Argentina’s expansive welfare state, which devours three-quarters of the annual government budget.

Inflation and unemployment picked up as market confidence in Macri’s economic plan plummeted. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed to bail out Argentina with a $57 billion loan, the largest in IMF history. Now Argentina is struggling to honor her financial commitments and the menace of default looms large yet again.

Content

- What is the state of Argentina’s economy?

- How much outstanding debt does Argentina have? What is her credit rating?

- Who will lead debt negotiations? What have creditors said?

- Is the new government willing to repay Argentina’s IMF loan?

- What is the incoming administration’s plan to turn the economy around?

- What have been the first economic measures?

After a four-year hiatus, Argentina resumed her predilection for socialist governments by swearing Alberto Fernández into office in December 2019. Like many Argentine presidents before him, he faces the huge challenge of steering the Argentine economy out of a self-inflicted crisis.

Mauricio Macri, the outgoing conservative president, failed to live up to his promise of poverty reduction and liberalization. Rather than tackling the root causes head on, he adopted a gradualist approach leaving untouched Argentina’s expansive welfare state, which devours three quarters of the annual government budget.

Inflation and unemployment picked up as market confidence in Macri’s economic plan plummeted. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed to bail out Argentina with a $57 billion loan, the largest in IMF history. Now Argentina is struggling to honor her financial commitments and the menace of default looms large yet again.

What is the state of Argentina’s economy?

Argentina has the third-largest economy in Latin America, after Brazil and Mexico, with a GDP of $470 billion. However, she has moved in and out of recessions over the last decade. In 2018, her GDP per capita fell to $11,683, a return to 2010 levels. The IMF estimates the economy contracted 3.1 percent in 2019, while inflation reached 55 percent.

During the Macri administration, 21,500 small and medium enterprises (SMEs) shut down, pushing the unemployment rate to 10.1 percent. Half of the workforce remains in the underground economy, and the poverty rate hovers around 40 percent.

In addition, Argentina faces a growing trend of capital outflow. Administration after administration has failed to convince Argentines to keep their money in Argentina, exacerbating the chronic shortage of US dollars. During Macri’s tenure, at least $72.2 billion left the country.

How much outstanding debt does Argentina have? What is her credit rating?

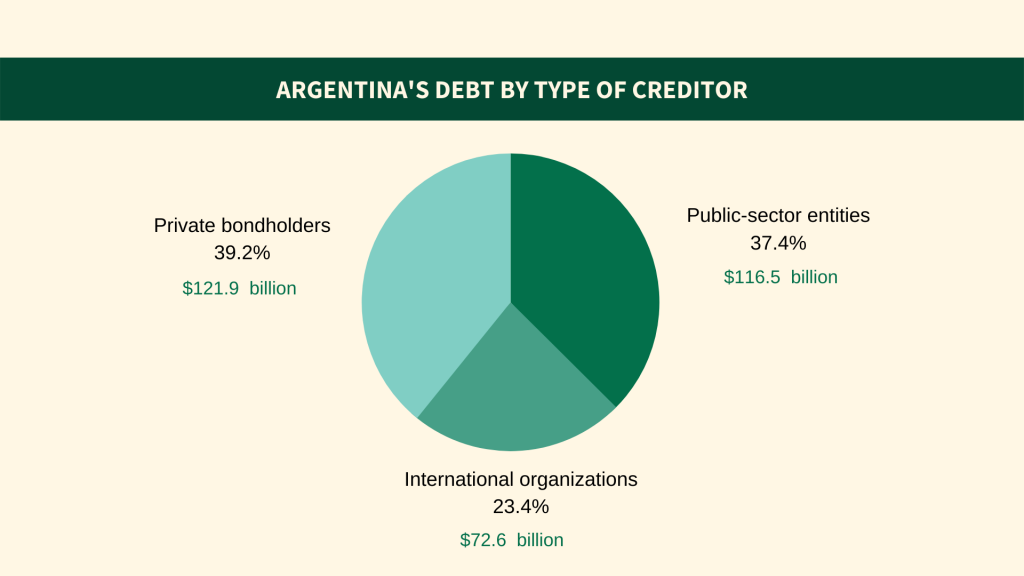

By September 2019, the Argentine government registered a total of $311.25 billion in debt, which accounts for 91.6 percent of GDP. Of this, 37.4 percent is with local government entities such as state-run banks; 23.4 percent is with international organizations such as the IMF and the World Bank; and 39.2 percent is with private bondholders.

Country risk—the spread between Argentine and US sovereign bonds calculated by JP Morgan—increased to 1,854 basis points after the provincial Buenos Aires government announced on January 13, 2020 its intent to delay payment of its 2021 bond. Argentina’s long-term issuer rating is Caa2 by Moody, CCC- by S&P, and CC by Fitch.

Who will lead debt negotiations? What have creditors said?

The new economy minister, Martín Guzmán, will lead the negotiations. He is a 37-year-old economist with a doctorate from Brown University. Before his appointment, he was a research associate at Columbia University, where he worked with the Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz examining how countries address default due to high foreign debt.

In addition, Matías Kuflas, minister of productive development and former Central Bank director, and Central Bank staff will assist Guzmán.

Their objective is to get an agreement with the IMF first and then ask private investors for more time to pay the country’s US$105 billion debt. The government has not revealed the whole plan yet, but it offered to keep paying the debt during negotiations.

The provincial Buenos Aires government complicated matters by asking creditors for temporary relief for its $227-million payment towards the 2021 provincial bond due on January 26. Four days before the deadline, creditors did not reach the required 75 percent consensus, so the provincial government postponed the time limit for bondholders to decide. The province is on the verge of default.

Creditors were already expecting a debt-restructuring deal, given the nation’s economic conditions. However, the new administration’s initial lack of clarity annoyed and worried them. After Congress approved the emergency economic plan on December 20, 2019, investors calmed down, and the Argentine 2020 bonds even increased by 28 percent.

Back in 2005 and 2010, a group of defaulted bondholders sued Argentina for full payment, citing an equal treatment clause. To avoid similar conflicts this time, investors are trying to find out if the “uniformly applicable rule” applies to this restructuring.

According to Bloomberg, this rule “sits in the collective action clauses (CACs) that comes into play in case of a debt restructuring. If the government chooses to sign a single accord with bondholders, the clause implies all investors have to be treated the same—whichever bond they hold and whatever its current value.”

Is the new administration willing to repay Argentina’s IMF loan?

Unlike the 2001 financial crisis, the new Argentine administration claims a desire to honor its commitments with the IMF. However, after holding his first meeting with the IMF director, Martín Guzmán said that Argentina prefers not to take the remaining $11 billion from the approved IMF loan to avoid accumulating debt. Guzmán also warned the IMF would not have any say in the country’s economic direction.

President Fernández aims to finish negotiations before March 31, whereas the IMF plans to send a delegation to Argentina in late January to start discussions. Alejandro Werner, IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department director, has voiced his support of the new government’s economic policies.

What is the new government’s plan to turn the economy around?

Central Bank President Miguel Pesce claims the government will boost the economy by cutting interest rates while fighting inflation through a “social contract” with businesses and labor unions.

Despite enacting currency and capital controls, Pesce announced the central bank will give privileges to oil and export-oriented industries.

Pesce also explained he seeks a reversal of the Macri administration’s economic policies, which included simplified regulations for doing business and a slightly elevated role for private actors.

In addition, Guzmán said on January 21 he seeks to negotiate a 50 percent discount on interest-rate payments and a two-year grace period. Nevertheless, Buenos Aires-based economists Marina Dal Poggetto—executive director at Estudio EcoGo—and Diego Ferro—president at M2M Capital— believe the government’s plan lacks consistency and transparency.

What have been the first economic measures?

- In December, the new Central Bank administration cut interest rates twice. The key rate floor fell in January to 50 percent—still the highest in the world.

- Congress passed the Law for Social Solidarity and Productivity Reactivation introduced by President Fernández. It authorizes the government:

- To declare a public emergency in the economic, financial, fiscal, administrative, pension, energy, health, and social sectors. This allows the president to enact reforms without the legislative branch’s approval.

- To impose a 30 percent tax on purchases abroad by Argentines and on foreign-currency purchases. It maintains the Macri-era $200 monthly limit on dollar purchases per person. From the new tax revenue, 67 percent will go to pension programs, 30 percent to infrastructure, and 3 percent to a new credit fund for farmers.

- To freeze electricity and gas utility bills for 180 days and public-transport fares for 120 days.

- To gradually increase the personal-assets tax.

- To increase export tariffs on farming by 3 percent.

- Two pension increases of up to US$84 for beneficiaries who earn less than $334 per month.

- Higher tax rates on vehicles, income, and corporate cash withdrawals.

- The addition of 310 goods to the price-control regime and an 8 percent reduction in the prices of medicines.

- The government ordered a pay raise of $66 for private-sector workers, which will take effect in March. The minimum monthly wage is $280.

- A new subsidy for low-income families, who will receive a monthly allocation based on the number of children.

- The freezing of gasoline prices, which are 15 percent below international market levels.

- On January 21, Guzmán sent a bill to Congress outlining his plan to renegotiate the nation’s debt. It would provide the executive branch with the legal power to structure and execute the required operations without congressional approval.

Previous Coverage

“Incrementalism Has Failed Argentina,” by Daniel Duarte.

“Argentina’s Taxes the Fastest Rising in Latin America,” by Paz Gómez.

“Argentina Defaults on Gas Payments, Foments Standoff with Bolivia,” by Paz Gómez.

“Warning: Argentine Default Imminent,” by Fergus Hodgson.