Public spending in Argentina from 2002 to 2016, which included the Kirchner era, ballooned in real terms by 70 percent. This growth surpassed that of any other nation in Latin America, according to a new report from the Argentine Institute for Tax Analysis (IARAF).

On August 12, the IARAF released its report, written by Nadin Argañaraz and Florencia Maldonado, comparing the tax-burden indicator of OECD countries with Argentina’s several tax rates and national budget.

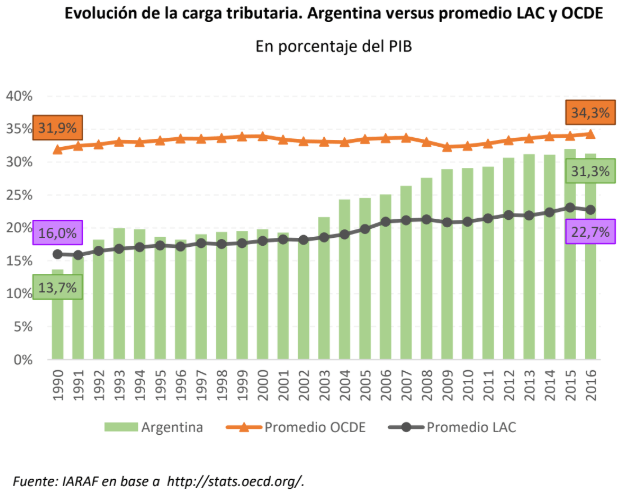

The effective tax burden for Argentines grew two times more than for other Latin Americans, according to the nonprofit and privately funded IARAF. Taxes eat up 31.1 percent of Argentina’s GDP, a burden similar to that of developed countries and almost 10 percent higher than that of her Latin-American and Caribbean peers.

The major factors driving the increase in public spending were current expenditures such as salaries and an all-encompassing welfare state, the report found.

Government Largesse Begets Tax Hikes

Social-security contributions and the value-added tax (VAT) explain most of the increase in the tax burden, followed by the national income tax and the provincial gross income tax.

The report recalls that in 2008 the government nationalized management of retirement and pensions. Since this move alone cost about 1.2 percent of GDP, it was a major boost to the tax burden.

This high-tax environment evidently came about as a consequence of greater public expenditure. Government spending shot up to 42.4 percent of GDP in 2016 from 24.8 percent in 2002. This period roughly coincides with the rise of Néstor and Cristina Kirchner, the populist left-wing politicians who ruled Argentina from 2003 to 2015.

The report identifies the usual culprits: public-sector payroll increased by 4.8 percent, social security by 4.1 percent, and contracts with the private sector by 3.9 percent.

During the government of Cristina Kirchner, for instance, the public-sector payroll almost tripled in size—even after adjusting for 500 percent inflation. The Kirchner administration heavily subsidized public utilities, universities, but also anything from train tickets to films, soccer clubs, and televised broadcasts of soccer matches.

In total, government expenses increased by 85 percent, leaving Argentina no choice but to reach out for loans. The government turned to debt, which in turn increased the public deficit.

“Argentina’s fiscal dynamics in recent years have led to an unsustainable structure: high public spending, high taxation, and high deficit,” Argañaraz argued in an op-ed on local newspaper Clarín.

This quagmire has been the most pressing challenge for President Mauricio Macri, of the Cambiemos centrist coalition, who had to enact unpopular austerity measures after he succeeded Cristina Kirchner in December 2015.

A Fiscal Anomaly

Argentina’s tax-burden rise of 12.88 percent from 2002 to 2016 eclipsed even that of OECD countries with larger economies such as South Korea, whose tax burden grew 4.4 percent over that period. In Latin America, only the Bahamas, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and Belice came close but remained below 10 percent.

The tax burden has increased substantially throughout Latin America and the Caribbean over the last two decades, just at a lower rate. In 1990, the average tax burden was 13.7 percent of GDP. In 2002, it rose to 18.4 percent, and it kept growing to 22.7 percent by 2016. Argentina’s tax burden, as mentioned before, went well beyond the average to 31.1 percent, a figure closer to the Western European average than to Latin America’s.

Despite Argentina’s alarming increase, Cuba—with 41.7 percent of GDP—and Barbados and Brazil—with 32.2 percent of GDP—remain the Latin-American countries with the highest tax burdens.

Toll on Economic Development

The World Economic Forum’s 2017 Global Competitiveness Index ranked Argentina 92 out of 137 countries. This report signaled that tax rates are the second-largest obstacle for doing business in the country. Inflation, policy instability, and regulations are other major factors.

Moreover, the Paying Taxes 2018 report, published by PwC and the World Bank, indicates that Argentina has the second-highest corporate tax rate in the world. Just after Comoros Islands, Argentine businesses have to spend at least 312 hours, or 39 labor days, to comply with taxes.

According to the head of the classical-liberal think tank Libertad y Progreso, Agustín Etchebarne, Argentines pay more than 100 different taxes and contributions to the national, provincial, and local governments. The country’s complex tax system is the reason why more than one-third of her economy remains in informal networks, he asserts.

Etchebarne believes that Argentina needs to simplify her tax system to reduce the burden on the economy. “Of course,” he says, “for this to be possible, it should be accompanied by a state reform that allows for reduced public spending.”

The Macri administration spearheaded a fiscal-reform initiative to reduce corporate tax rates and signed an agreement with the provinces to reduce the tax burden by the end of 2017. The first stage of the law is already underway, and a second phase will begin in 2019.

Lackluster Economic Recovery

Argentina is the 21st largest economy, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), but the South American nation has faced nothing but trouble over the past years. Stagflation has characterized Argentine markets since 2011 due to the price and exchange controls enacted during the Cristina Kirchner administration and the rising debt and deficit levels.

At 30 percent, the annual inflation rate is among the highest in the world.

The Macri administration finalized a $50 billion relief package with the IMF on August 13, 2018. In exchange, Argentina has to keep her national debt under 65 percent of GDP this year and then lower it further. Deep cuts in payrolls and entitlements will pose severe political challenges for the national government.