The moving company that hired me in my early 20s sought university graduates for long-term positions. Perhaps you had a different experience, but my formal education never covered how to move pianos or drive trucks.

This anecdote is one of countless others we have all witnessed with an obvious mismatch between education and employment. When I began work as a reporter, for example, experienced campaigners recommended that aspirants avoid communications or journalism degrees.

You will learn your trade on the job, they explained, ideally as soon as possible via internships. For those dead set on university, the recommendation was for technical majors, such as finance or statistics. These would allow one to distinguish himself and target a niche.

Notwithstanding disparities across academic fields, the mantra that university students garner job skills and “learn how to learn” does not jibe with personal experience. Students by and large celebrate if a professor cannot deliver a class. Yet we are supposed to believe their chief motive for going to college is education.

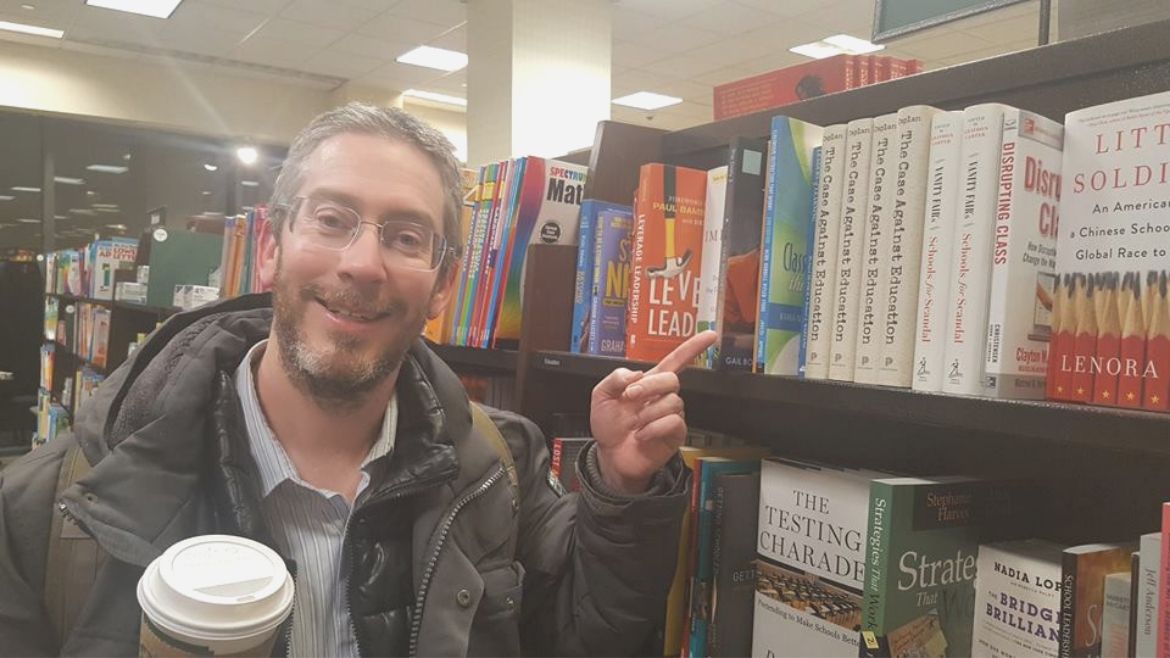

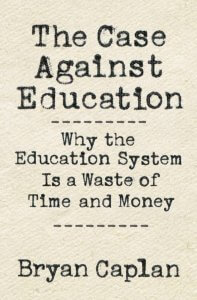

Bryan Caplan, a George Mason University economics professor, confronts the higher-education riddle in his latest book, The Case against Education (400 pages, 2018). He explains how higher education has sprawled so vastly, despite students learning so little. His conclusion is that signaling is the greatest motive and benefit to students.

A university degree is a stamp of approval that someone possesses desirable traits: intelligence, conformity, and conscientiousness. His analogy is that you can approach a diamond in two ways. You can certify it or you can refine it. Universities certify graduates by making them jump through countless hoops and satisfy their professors. This explains why there is little payoff to incomplete programs that should provide human-capital returns.

The profound irony of The Case against Education is that it delivers a case for education on an individual basis. There is a healthy premium for those who graduate, at least in a preponderance of cases. The book is data heavy, and Caplan’s estimate is that over half of the earnings disparities we observe between education levels are attributable to degrees held.

Of the degree-derived portion, Caplan contends 80 percent or more boils down to signaling. That is why getting degrees makes sense for the individual but not for the broader economy. Although you may get ahead and show off by getting another degree, if we all receive subsidies to study, the process becomes increasingly difficult and costly. Status is relative, so you cannot raise everyone’s status at the same time.

If signaling is what universities are selling and what taxpayers are paying for, the exercise is a colossal waste. Caplan devotes his final chapters to assessing alternatives and arguing for major reductions to or outright elimination of state subsidies for higher education.

As a moderate but better option than the US approach, Caplan offers Switzerland as an example of an extremely competitive but limited higher-education sector. In the QS World Rankings, the nation with 8.5 million inhabitants has seven universities in the top 200. That is as many as Canada, which has four times the population.

For those without a natural affinity towards university, the Swiss emphasize trade schools and apprenticeships. This means people can better match their education with their interests and avoid entering a welfare-dependent underclass.

The most value in the book is in the first five chapters, which assess the merits of specific university majors and programs for individuals. As Caplan acknowledges, he is not holding his breath for a turnaround to the near-universal pandering to universities from politicos. The news you can use is his analysis for your own decision making. Why he takes an anarcho-capitalist or libertarian view of education seems less compelling, especially if you are already one of the converted.

Critics immediately point to Caplan’s doctorate from Princeton University and his work as a professor at George Mason University. However, he believes his credentials give him more credibility on the topic, and he styles himself as a whistleblower. In his role, he witnesses the saddest aspect of artificially incentivized university education: boredom among the students. They don’t want to be there, so most feign interest and just do what they must to pass and get on with their lives.

Caplan covers a lot of ground, including an explanation for why alternatives have struggled to pop the so-called higher-education bubble. Throughout, he does his best to draw on all the available academic research, so the book is handy for academics and the layman.

There is a hint of condescension towards those who are not professional intellectuals, although likely unintended. He just expresses disappointment that rarely the instruction stays in students’ brains or gets applied outside the classroom.

Regardless, The Case against Education stands as extremely important for the way it challenges our time’s education dogmas. His nuance does not fall neatly into either camp of critics or proponents, but his narrative explains that both are right. Universities struggle to teach, but diplomas are increasingly important for vocational prospects. The logic follows that taxpayer funding mostly delivers a downward spiral of wasted years in hollow programs.