Gabriel Boric took office as the new Chilean president on March 11, 2022—a turning point in the country that went through a three-year political crisis. Nationalizing lithium will be one of his first moves toward growing intervention and central planning.

During the campaign, Boric offered to nationalize lithium. He announced on social media that “Chile cannot again commit the historic mistake of privatizing resources, so we will create the National Lithium Company, generating jobs in their reservoirs and a Chilean seal on the product.”

As global demand for the so-called white oil rises, expectations regarding the future of the lithium industry in Chile will also increase. Nationalization, however, is set to hinder the sector’s growth.

What Is the Current State of Lithium Production in Chile?

In 2019, Chile became the second-largest producer of lithium in the world, just after Australia. With a 29 percent stake in the global market, the country exported $931 million in lithium.

If the country doubles production by 2030, exports will reach levels of wine exports, which equaled around $2 billion in 2019. Moreover, the Chilean lithium industry will consolidate and remain competitive with an estimated 17 percent stake in the global market.

Chile currently exports the raw materials for batteries: lithium carbonates and hydroxide. The main trading partners are South Korea, Japan, China, Belgium, and the United States.

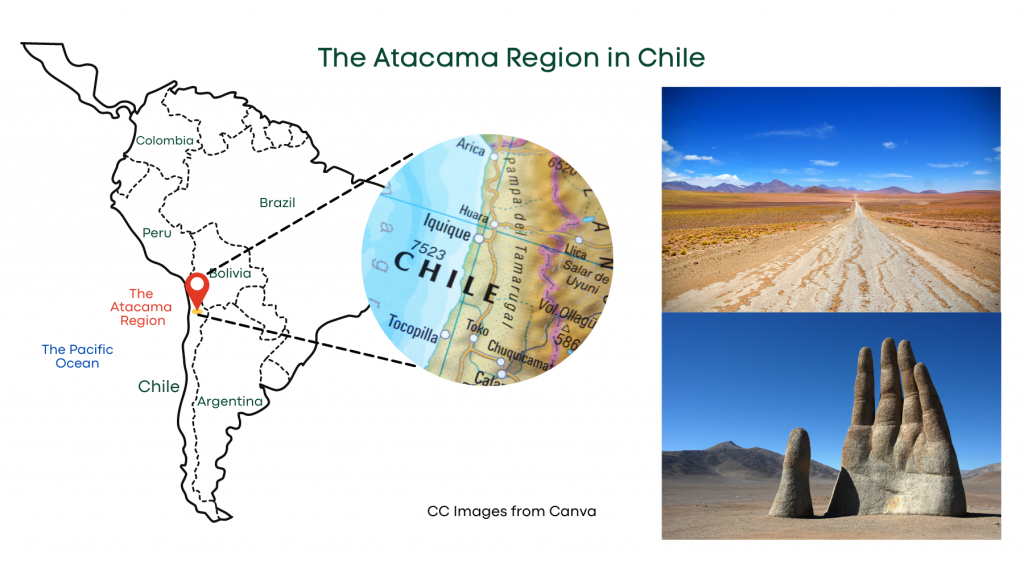

Albemarle, headquartered in the United States, and local SQM are the companies that produce lithium in Chile. The government’s entrepreneurship promotion agency Corfo has provided them with the license to operate in the Atacama region.

In October 2021, the Sebastián Piñera administration called private companies—local and foreign—for a tender to produce 160,000 tons of lithium. On January 12, 2022, the government awarded 20-year contracts to the Chinese car firm BYD and Northern Mining Services and Operations S.A, a company that forms part of an enterprise conglomerate in Chile.

The same day, Boric criticized the decision as an act of cronyism performed at the last minute of the outgoing administration. An appeals court halted the contracts on January 14 under the argument of incomplete procedures, and the contracts remain stalled.

How Will Chile Nationalize Lithium Production?

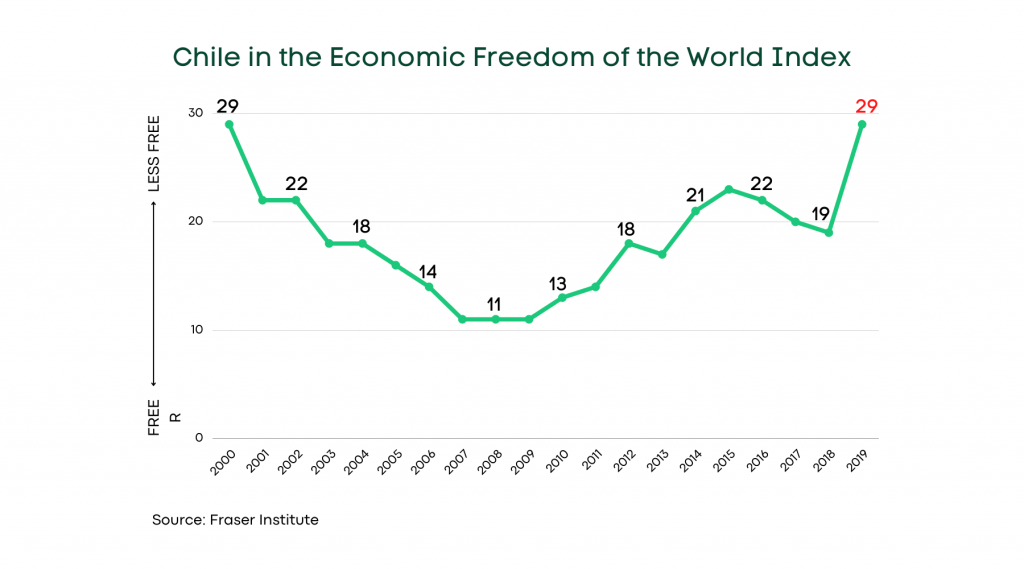

Chile has been the freest Latin American economy for decades. As such, it has enjoyed solid private sectors in most industries, including mining. However, a growing trend of public opinion in the country favors central planning, wealth redistribution, and natural-resource nationalization.

This stance was evident on March 5, 2022. The primarily young advocacy leaders of the environmental commission at the Chilean Constituent Assembly—those writing the new constitution—introduced a motion to nationalize large-scale mining firms and revoke contracts in environmentally sensitive locations.

To be part of the new constitution, the proposal needs two-thirds approval from constituents. Citizens will have the final decision through a referendum at the end of the year.

Boric, however, can take steps in advance. In his governance plan, he proposed a comprehensive reform in the mining industry to give the state a prominent role. The proposal includes lowering carbon-dioxide emissions and stressing community development.

Regarding lithium, Boric has proposed a state-run company to control production procedures, initiate scientific research, and promote the manufacturing of value-added products. By nationalizing the industry, he expects to raise government revenues and create more jobs in the public sector.

What Are the Consequences of Nationalization?

Due to the global energy transition towards renewables, lithium prices increased by nearly 80 percent in 2021. White oil will become more attractive as the adoption of electric vehicles rises.

Since Latin America is home to the largest lithium reserves in the world, politicians in the region have rushed to find ways to increase public budgets through lithium production revenues. Officials in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru have considered the idea of creating a lithium cartel similar to OPEC to ensure stable lithium prices.

Although the nationalization trend is relatively new in Chile, the region has a long-standing tradition of relying on natural resources and controlling their production from the government. In the name of strategic growth and community development, officials have ruined industries: oil in Venezuela, energy in Nicaragua, beef and dairy in Argentina, and more.

In Chile, lithium could become less attractive if nationalization policies undermine legal certainty and increase supply-chain costs. By creating a national lithium company and removing mining firms, Chile could also lower production quality. Limiting production quantities could also impede economies of scale.

Nationalization advocates argue that Chile should not export raw materials but manufacture derived products such as batteries. Central planning, however, is usually short-sighted. In this case, it disregards the fact that manufacturing batteries would require importing materials from China, the global leader in battery production.

Additional risks are corruption and negligence. While private mining companies have the pressure of market forces and shareholder accountability, public servants can misspend taxpayer money with few or no long-term consequences for themselves.

Can Chile’s Lithium Still Remain Competitive?

Chile is the world’s leading copper producer and has one of the largest lithium reserves. Both are advantages for Chile, but the lithium market is emerging and its future is uncertain.

Lithium is not an absolute requirement for battery production; manufacturers can opt for other materials if the costs to obtain lithium increase. Moreover, Chile is facing harsh economic conditions with recession and inflation.

The political crisis that began in 2019 pushed capital out of the country and branded Chile as a riskier and more unstable nation. Moreover, according to the US State Department, the permitting process for mining in Chile is already contentious due to burdensome environmental assessments, water-rights issues, and indigenous consultations.