Content

- How is Cuba’s economy weathering the pandemic?

- What does the monetary unification entail?

- Are there other economic reforms underway?

- How are these reforms impacting Cubans?

- Is Cuba finally leaving socialism behind?

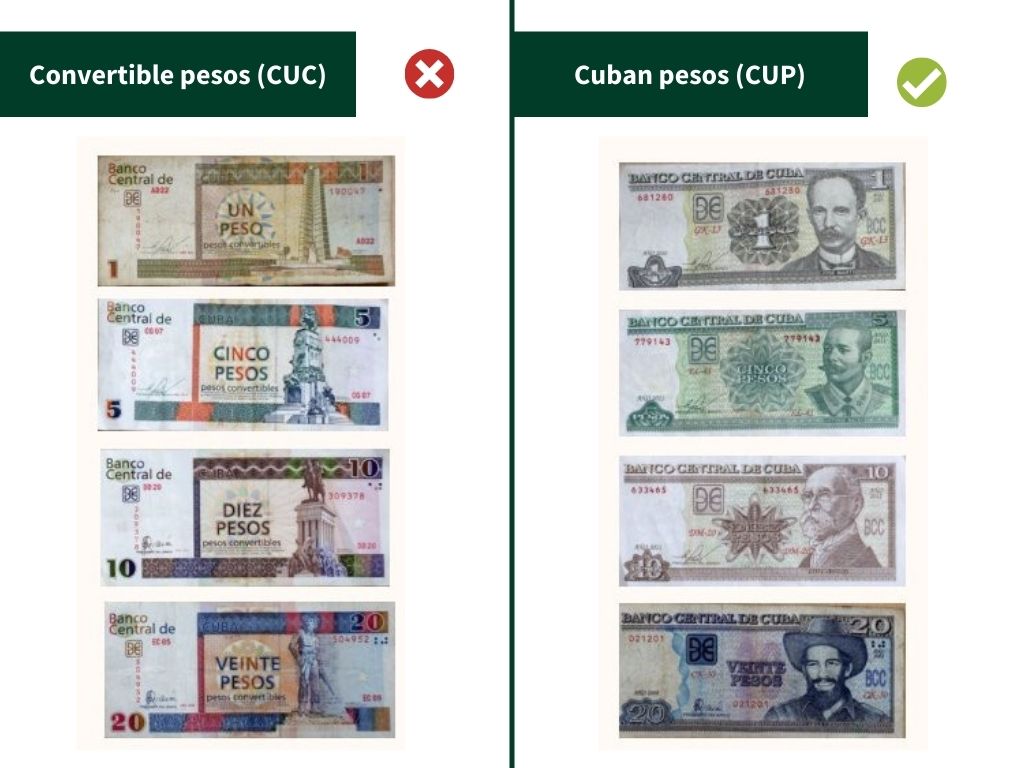

The pandemic has accelerated economic transformations across the globe. In Cuba, this has included liberalizing its economy and unifying the two official currencies: the Cuban peso (CUP) and the Cuban convertible peso (CUC). The harsh but long-delayed reform, effective since January 1, 2021, has triggered a rapid devaluation and price hikes in Cuba.

.

.

How is Cuba’s economy weathering the pandemic?

The Communist Party of Cuba has been ruling the country for over six decades through a family dynasty started by the late Fidel Castro. Even though his successor and brother, Raúl Castro, formally stepped down in 2018, the current Cuban head of state, Miguel Díaz-Canel, has limited decision-making power. Castro still leads the ruling party and the military, which controls most of the economy.

The little information that Cuba’s government provides about its state-controlled economy is unreliable, and official statistics depict an incomplete picture. For instance, Cuba’s 2018 GDP per capita of US$8,821 flies in the face of a regular Cuban’s monthly average earning of $25–$30 per month.

In addition to a health crisis, the pandemic brought about a 50 percent decline in imported goods, which are vital in an economy with few, unproductive industries. This has exacerbated food shortages and waiting lines for government handouts.

The scarcity of medical supplies and hygiene products has undermined the pandemic response. Businessmen living abroad in countries with no trade restrictions with Cuba, such as China and Vietnam, have sent humanitarian donations to support the government’s relief efforts.

Furthermore, remittances, a key revenue source for Cuban households, shrank by at least 54 percent in 2020, according to a report from the Havana Consulting Group. Along with the disappearance of tourists, Cuba has run out of most foreign-capital revenue.

In 2020, the Cuban economy saw the worst decline in three decades: an 11 percent fall in GDP according to government figures, which means it was likely even larger. This came on the back of prepandemic stagnation years; the average growth from 2016 to 2019 was 1.2 percent.

Underscoring that Cuba is on the verge of bankruptcy is the country’s request to pause Paris Club debt repayments until 2022. Although the government blamed it on the pandemic, Cuba already missed around $35 million due in 2019. Further, Cuba had renegotiated its foreign debt in 2015, when the Paris Club agreed to forgive three-fourths of loans.

With no other solution on the horizon—as tourism, remittances, and imports continue to dwindle—the Cuban government opted to usher in a new economic order that includes a greater role for the private sector and the phasing out of CUC.

.

.

What does the monetary unification entail?

The Cuban regime created the convertible peso (CUC) 26 years ago. It is a US dollar-pegged currency mainly used by the Cuban elite and tourists. Daily transactions for most Cubans involve the Cuban peso (CUP), which has an official exchange rate of 24 CUP per US dollar. Keeping the artificial exchange rate throughout the years has demanded a steady flow of US dollars.

The pandemic, however, made that equation untenable. The monetary unification means the CUC will be no more by mid-2021. Thereafter, the sole legal tender will be the CUP. This reform, however, is not new. The Cuban government announced it for the first time eight years ago but kept delaying its implementation due to the predictable impact on prices.

A warning sign came in August 2019, when the government converted 72 state-controlled stores into dollar shops. To collect sound money, these stores only accept US dollars and other foreign currencies such as euros and pounds through credit cards—no cash is accepted.

.

.

Are there other economic reforms underway?

Besides the monetary unification, the Cuban regime had to overhaul its price-fixing policies and subsidies in order to boost the private sector, which it sees as a lifeboat out of the current crisis.

Prices and Wages

The government announced higher prices for 42 staple goods, including fuel, electricity, running water, sugar, coffee, milk, and toothpaste. A loaf of bread is now 20 times more expensive. Salaries increased too, but to a smaller extent, igniting widespread discontent. After protests, the regime had to backtrack on the electricity hike.

The monthly minimum wage went from 500 to 1,200 Cuban pesos (roughly $21 to $50). On average, salaries in the public sector increased by 5 percent. The government, however, did not disclose the raises for senior officials such as Díaz-Canel and Castro.

Subsidies

In Cuba’s socialized economy, citizens rely on the government to provide nigh everything at artificial prices. The regime has started a gradual reduction of subsidies for nonessential goods and services. For instance, cuts do not apply to baby formula, pregnancy supplements, and dairy products.

Telephone services and transportation did get more expensive. In a similar vein, government cash transfers to state-run firms will fade away to encourage competitiveness.

.

.

How are these reforms impacting Cubans?

The immediate effect has been tough, leading to widespread unrest. Higher prices and lower subsidies have forced those who lived on handouts to seek jobs. However, opportunities are scant in a private sector throttled by decades of government bans.

Juventud Rebelde, a government media outlet, released on February 15 the first survey on Cubans’ perceptions of the economic reforms. Of 511 respondents, 39.2 percent said they could not make ends meet despite the higher salaries. Thirty-seven percent argued the reforms had been untimely, and almost half believed they were a step in the right direction.

Harold Cárdenas, a Cuban political scientist exiled in the United States, remains skeptical. The policies will only be a success if the government somehow boosts job opportunities soon, he argues.

In a similar vein, Cuban journalist Carlos Montaner predicts these economic reforms will not lead to political ones. He argues citizens may end up enjoying a better quality of life, giving the totalitarian regime some breathing room to remain in power.

.

.

Is Cuba finally leaving socialism behind?

According to Díaz-Canel, the reforms seek to make the economy more efficient and attract foreign investment. The government also expects Cuban manufacturers to become more autonomous and productive, lessening the country’s dependency on imports. However, Cuba is taking a page out of China’s move toward state capitalism, not free markets.

Montaner explains Cuba continues to be a centrally planned economy. The Cuban regime will keep a stake in the opportunities it opens up to private investment, creating a new crony economy.