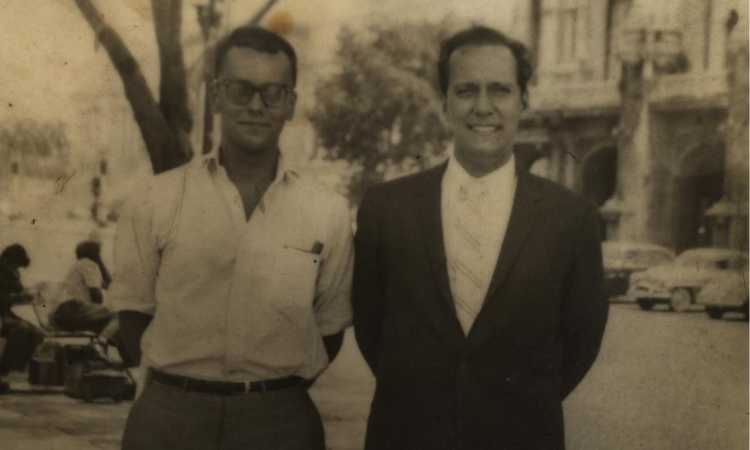

Brothers from Time to Time by David Landau tells the extraordinary true story of two brothers who play diametrically opposed roles during the Cuban Revolution and its aftermath. Although far from a history lesson, their firsthand accounts present a unique view unlikely to be found in the legacy press.

The plot is straightforward. Emi, the elder brother, is a Cuban patriot. He is infuriated by the corruption of the second Fulgencio Batista regime (1955–1959) and devotes himself to its overthrow, joining Fidel Castro’s revolution. Eventually, Emi sees the new communist regime for what it is and again devotes himself to battling for the freedom of the Cuban people.

Adolfo, the younger brother, also fights for the Cuban Revolution against Batista. However, unlike Emi, Adolfo is a devout, idealistic member of the Communist Party. As Castro takes control of Cuba, Emi becomes a party spokesman and youth leader.

After many years of scheming, activism, and imprisonment, both brothers eventually flee Cuba for the United States. Older and wiser, they reconcile.

After many years of scheming, activism, and imprisonment, both brothers eventually flee Cuba for the United States. Older and wiser, they reconcile.

Landau’s book contains all the elements of an espionage thriller: CIA plots, guerrilla warfare, false identities, Havana safe houses, and prison interrogations. However, someone expecting the book to read like a John Le Carré novel will be disappointed. Espionage plays a small part in the overall story. Any reader expecting a history of the Cuban Revolution or a comprehensive look at socialist Cuba should look elsewhere.

This book will resonate with readers already familiar with the history of the Cuban Revolution, necessary to fully understand the brothers’ stories. Few lives conform to a storybook narrative, and these lives are no exception. What makes Brothers from Time to Time interesting are the glimpses, snapshots, and various points at which the two lives intersect and bear witness to the brutal Castro regime.

The book goes beyond the usual portrait of Castro as a dashing, charismatic Robin Hood. Landau also provides glimpses of Castro’s hubris as an inept economic meddler sabotaging his own bureaucrats and a totalitarian murderous thug who launched ruthless purges of potential rivals or traitors.

Although biographical and chronological, the book is by no means a complete account of the brothers’ lives. Instead, Landau selects intermittent episodes where the brothers played a role or witnessed a significant event during this tumultuous era of Cuba’s history. This approach necessarily lacks continuity, sometimes jumping years spanning the Batista regime, the Cuban Revolution, and the ensuing five decades of Fidel Castro’s rule.

Landau has resisted the urge to dramatize or narrate to excess. Instead, he relies on the direct recollections of the two brothers, cobbling them together, switching from Emi’s world to Adolfo’s. Letting the story unfold this way is less fluid and polished but rewards the reader with a more authentic and unvarnished grasp of the events as they transpired.

As tragic as the life trajectories of Emi and Adolfo were, they ended their days with the wistful knowledge that they had lived lives with purpose. Perhaps the greatest sadness is that it took so long for their accounts to see the light of day. One cannot help but wonder if history and the sad plight of the Cuban people might have been better served had this book been published at an earlier time.