Left-wing guerrillas lower a city’s tax revenue and property rights, while right-wing paramilitaries increase them. Surprising? A new research paper has gathered evidence from Colombia’s decades-long conflict between these two factions.

Colombia has endured six decades of internal warfare between guerrillas, paramilitaries, and other criminal groups. However, she was supposed to turn the page in 2016 after the highest-profile combatants, the Marxist FARC rebels, surrendered, although the agreement was highly controversial and rejected by Colombian voters in a referendum.

Now the International Red Cross is saying it will take “decades” for lingering violence to subside. Coca cultivation and drug trafficking are also on the rise. “No one counted on the government being so slow in arriving in [previously occupied areas],” Ariel Ávila, a political analyst at the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation in Bogotá, told Bloomberg News.

State-Building versus Internal Rivals

Why are states, with their monopoly of force, unable to easily step in and retake control of their own territories? Why does a militarily capable state such as Colombia need decades to defeat internal rivals? Political scientists and historians have long struggled to explain this phenomenon.

Endogenous Taxation in Ongoing Internal Conflict: The Case of Colombia, a paper that appeared on August 3 in the American Political Science Review, adds a fascinating approach to studying internal conflicts. The authors—researchers from the United States, the Netherlands, and Colombia—have shown that armed groups can successfully prevent state-building by capturing and altering local institutions to their preferences, with lasting effects.

They picked Colombia because, among other reasons, her roughly 1,120 municipalities have the authority to shape property and tax institutions at the local level, and the main combatants in the war had clear preferences regarding state-backed property rights.

On the one hand, the Marxist FARC guerrillas viewed state-recognized property as illegitimate and promoted land invasion to split up large parcels among peasants. They even imposed their own “revolutionary tax” in regions under their control.

On the other hand, right-wing paramilitaries that emerged to combat the insurgents, namely the United Self-Defenders of Colombia (AUC), favored landowners. The landowners supported them and didn’t see a problem in the accumulation of large parcels or intensive agriculture.

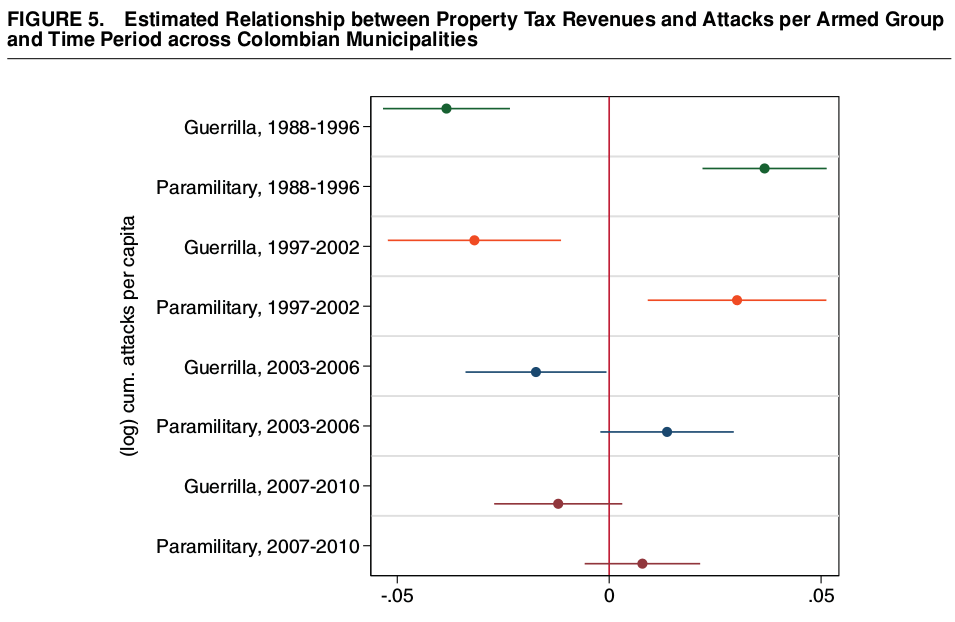

This dynamic led to brutal confrontation for territories, which the study traces over four periods: FARC ascendancy (1988-1996), paramilitary expansion (1997-2002), paramilitary demobilization (2003-2006), and state resurgence (2007-2010).

Whose Property Is It Anyway?

The authors set out to test whether the group’s ideological preferences led to a change in property rights and tax performance in cities they occupied, using data from land registries and tax revenues, which are managed by Colombian municipalities.

The study found a clear pattern: “municipalities with significant insurgent violence report less land formalization and lower tax receipts. Municipalities that experienced significant paramilitary violence have more land formalization and higher tax receipts.”

This would seem to suggest that paramilitaries favor state-building and even property rights, but there are important caveats. Land formalization is just one measure of property rights, and it says nothing of the origin or just acquisition of those titles. After all, paramilitaries displaced entire villages and robbed people of their lands. FARC members did the same; they just didn’t register the land because they didn’t believe in state registries.

“To legitimate this transfer of land, paramilitaries sought to formalize property through the state … public notaries, the officials charged with validating the provenance of land, were infiltrated by paramilitaries,” the authors note.

The violent groups influenced a city’s policies through basically three mechanisms: 1) they threatened mayors and councilors; 2) they got like-minded politicians elected; and 3) they indirectly influenced the economy through their violence.

Left-wing guerrillas mostly resorted to 1 and 3, since they shunned the electoral process and the democratic state altogether, while paramilitaries mostly operated through methods 1 and 2. The AUC backed many conservative candidates and carried out political assassinations that influenced electoral outcomes.

In other words, paramilitaries tried to legitimize their violence, which is why its effects appear on government records, while the FARC was content to remain an outlaw.

State Lessons

This isn’t a debate about choosing the lesser of two evils. Beyond its historical value, the study is useful for policymakers to address weaknesses in land reform, an often touted but unrealized promise in many Latin-American countries. Instead of blanket measures for the entire country, they should take into account how groups have tipped the balance in certain regions.

“In Colombia, for example, the state should focus on land redistribution and progressive taxation measures in areas where the paramilitaries were dominant. In areas where insurgents were dominant, attention to land formalization and tax collection should be prioritized,” the authors suggest.

It also shows the limits of government decentralization in countries with internal disputes over territories. The study warns that “while fiscal decentralization might maximize political economy goals in stable countries, it may also engender significant drawbacks in those experiencing ongoing violence. To restore the state’s control over local tax institutions and property rights, the central state may have to limit municipal autonomy.”

Alas, the study fails to model the state as another armed group exerting violence for its own ends. In Latin America, politicians campaign on distorted accounts of history to manipulate public opinion and justify policies benefiting their supporters. Corruption and cronyism are the order of the day. No wonder that former guerrilla and paramilitary members are already forming new organizations to keep profiting from the government’s failed drug war.

Until we incorporate this account into our analysis and start holding authorities accountable, we will continue to breed violent groups dissatisfied with the status quo.