Desperate to hold onto power, Rafael Correa and his cronies resorted to numerous schemes to win the 2017 presidential election. For more than a decade, they had ruled Ecuador at their will, imposing “official truths” and hiding wrongdoings thanks to a huge propaganda apparatus.

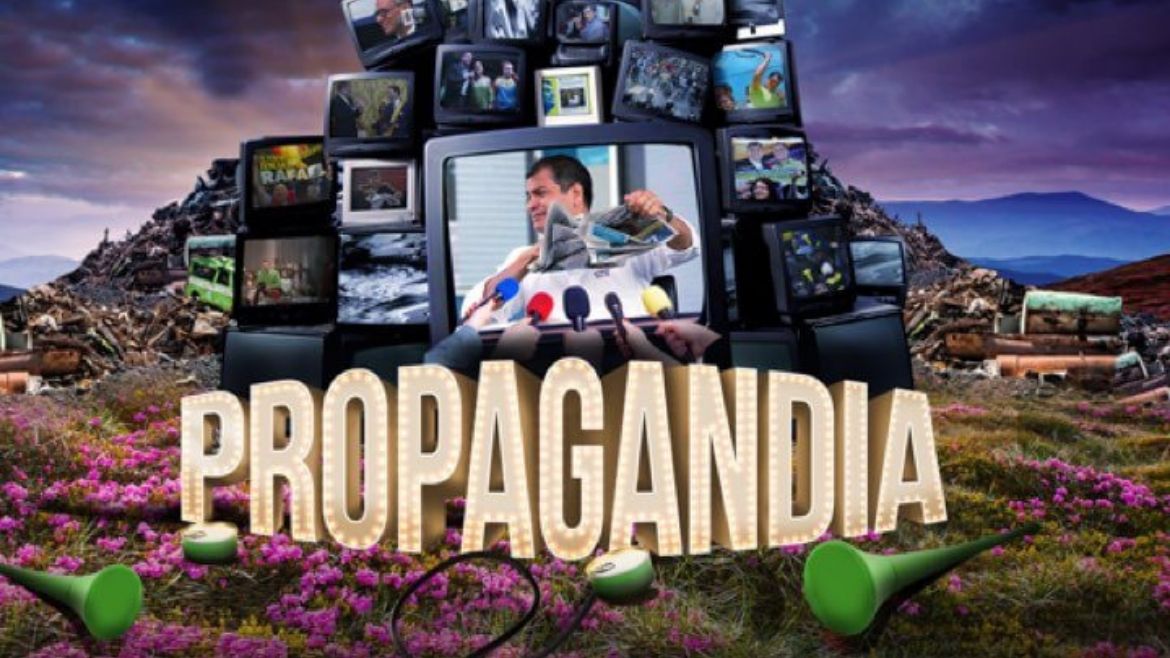

Carlos Andrés Vera, an Ecuadorian journalist and filmmaker, witnessed the ruling PAIS Alliance (AP) party’s abuse of power during the election. He documented the vote tallying process and produced a documentary called Propagandia, released in May of this year, exposing how the AP managed to stay in power.

The Correa administration ushered in an era of censorship, repression, and deceitful propaganda in 2007. These were also the tools that allowed the AP to expand its influence everywhere in the country. A decade later, the party could not fathom losing the election, even if that meant using government resources to shut down critics.

In an interview for the Ecuadorian outlet Plan V, Vera explained that “the documentary shows, in a chronological manner, how this [propaganda] apparatus was built, and how this apparatus reached its highest point in the last election.” When the AP realized that there was a real risk of losing for the first time, it used that apparatus “without remorse,” he said.

The ruling party itself did not necessarily commit electoral fraud, although there were notable irregularities. Rather, what Vera shows is the more extensive scheme of deceit and manipulation.

Electoral authorities were appointed arbitrarily, and they modified the vote tallying system to allow digital tampering and to avoid independent oversight. They threatened and intimidated people with key roles in the verification process, such as Ruth Hidalgo, president of the autonomous organization in charge of the preliminary vote count.

Hidalgo told her story for the documentary, still full of fear: how she was followed around for days; how every morning, while her young son waited for the school bus, two cars with tinted windows parked in front of her home. Her family and other members of the organization received death threats. Those who called wanted them to support the ruling party’s plan, she claimed.

The Correa administration also tinkered with official statistics to increase the public debt beyond the legal limit of 40 percent of GDP. Officials removed domestic debt from the total tally so they could borrow more money and buy more votes, pushing the real ratio to 52.54 percent of GDP.

That was just the start. On the one hand, Correa destabilized political institutions and overturned the rule of law, common tactics deployed in other countries also following the 21st-century socialism agenda. On the other, he pioneered marketing strategies that would make Joseph Goebbels jealous. In fact, one of his videos emulated a Nazi-era propaganda ad where Adolf Hitler climbed a hill in a windy, sunny day.

Luis Eduardo Vivanco, former chief editor of a popular newspaper in Ecuador, was one of the journalists interviewed for the documentary. “Real politics happens when the cameras turn off,” he said, accurately describing a government that targeted independent reporters, expropriated media outlets, and created friendly ones. Correa placed 29 media outlets under his control to work as his propaganda arm.

Ecuadorian journalists routinely engaged in self-censorship. “We had to work on a knife-edge to be critical but avoid lawsuits.” With the enactment of the Communications Law—better known in Ecuador as the Gag Law—and the creation of a state agency to censor journalists, the press was undoubtedly one of the most targeted sectors during Correa’s rule.

Those government officials who investigated and dared to denounce corruption also had to face retaliation. Opponents of the regime were particularly targeted. Guillermo Lasso, the opposition candidate in the 2017 presidential election, was himself a victim of the propaganda apparatus.

The documentary narrates how Lasso and his family were attacked at the end of a soccer match. One of his bodyguards claimed he prevented one assailant from stabbing Lasso in the back.

Vera also mentioned several overlooked deaths that occurred during Correa’s tenure, implicating the ruling party. The documentary did not elaborate on this issue due to the lack of solid evidence. However, the fact that the National Court of Justice has ordered Correa’s arrest for his alleged involvement in the kidnapping of political activist Fernando Balda demonstrates the urgent need to investigate other cases with loose ends.

In Ecuador, only one movie theater chain offered Propagandia nationally. It seems that the other firms preferred to avoid problems with the AP’s Lenin Moreno, the current president of Ecuador.

As many interviewees in the documentary explain, it is still uncertain where the new administration is heading. Moreno’s economic and foreign policies are vague, the public debt keeps growing, and many Correa followers still hold important government posts.

In the meantime, there has been some progress in recovering freedom of expression. The judiciary has pursued corruption probes diligently, but there is much left to dismantle Correa’s perverse legacy.

Editor’s note: we are not aware of a way to obtain this film online, but we will let readers know if that status changes.