There is an unavoidable and painful question on the lips of lawmakers, policy analysts, and media commentators throughout Latin America: why are Anglo-Americans so rich while we are so poor?

Astute researchers and public intellectuals have offered detailed and compelling answers to this question, including José Azel of Cuba and Carlos Rangel of Venezuela (see Reflections on Freedom and The Latin Americans). However, one book is distinct among its peers by precisely targeting this question and focusing on the failed 1990s series of privatizations.

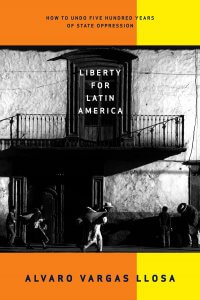

Although published in 2005, Liberty for Latin America—available in English and Spanish (Rumbo a la libertad)—is more pertinent than ever. Since its release, the cancer of 21st-century socialism has spread and metastasized. Those who see the problem need a viable alternative and an explanation for how it took hold so rapidly. Álvaro Vargas Llosa, a Peruvian exile who has been at the heart of the fight, is the man for the job.

Subtitled How to Undo 500 Years of State Oppression, this 315-page work distills the key reasons why the law and the state in Latin America have barely, if ever, had legitimacy. From the get-go of initial Spanish colonization, and even prior to the European arrival, Vargas Llosa demonstrates the presence of five pernicious habits: corporatism, state mercantilism, privilege, wealth transfer, and political law.

Latin-American institutions’ deserved lack of legitimacy has fostered wiki-constitutionalism and countless violent coups and revolutions, all to no avail:

Democracies behave like dictatorships … private enterprises like government bureaucracies … laws and constitutions amount to fiction … real people are forced to spend their lives struggling to survive in hostile environments.

Latin America remains, Vargas Llosa writes, “a symbol of oppression,” and even the many apparent overhauls have led to a “reshuffling of elites and power interests.” He contrasts these events with the “anti-revolution” of the United States, which intended to restore and continue an earlier order, a bottom-up natural law.

That does not mean the United States is as pure as driven snow, and Vargas Llosa notes correctly that she largely abandoned limited government after World War I. (Vargas Llosa is now a senior fellow with the Independent Institute, and he resides in Washington, DC.) One of the great tragedies of US-Latin America relations has been the drug war, unfortunately with largely complicit governments south of the Rio Grande:

The United States went to war by proxy against a profitable business that was impossible to halt. The senseless war against the laws of supply and demand raised prices artificially, and therefore the profits and power of the drug smugglers.

The book is far from a downer, though. After going to great lengths to explain what went wrong in the 1980s and 1990s, it offers a surprisingly realistic and inspiring path to liberal reforms.

First, despite the many errors of meddling foreigners, well-intentioned or not, Latin Americans must take responsibility for their own future. Far too many “have resorted to blaming international bodies for evils whose major causes lie at home.” Begging for handouts and loans has had the effect of “strengthening statism, postponing adequate solutions, and displacing political responsibility.”

Without dishing out all the dessert of the final chapter, one overarching theme strikes as pivotal: “Development cannot be decreed or legislated.… The institutions of civilization have resulted from a long evolutionary process, not deliberate design.”

Positive reforms toward laissez-faire capitalism within the context of liberal democracy will require humility on the part of each nation’s political class. Vargas Llosa explains in an easily understandable fashion how such a process could proceed, “cleansing the law and sanctifying the choices of the poor … [and] empowering the justice system.”

Vargas Llosa’s contribution to the field of economic development—a precise, in-depth explanation for 1990s reform failures and a compelling path forward—is historic. His book justifiably earned the 2006 Sir Antony Fisher International Memorial Award, and it deserves to be read by all Latin Americans and allies who do not wish to repeat the failures of the past.