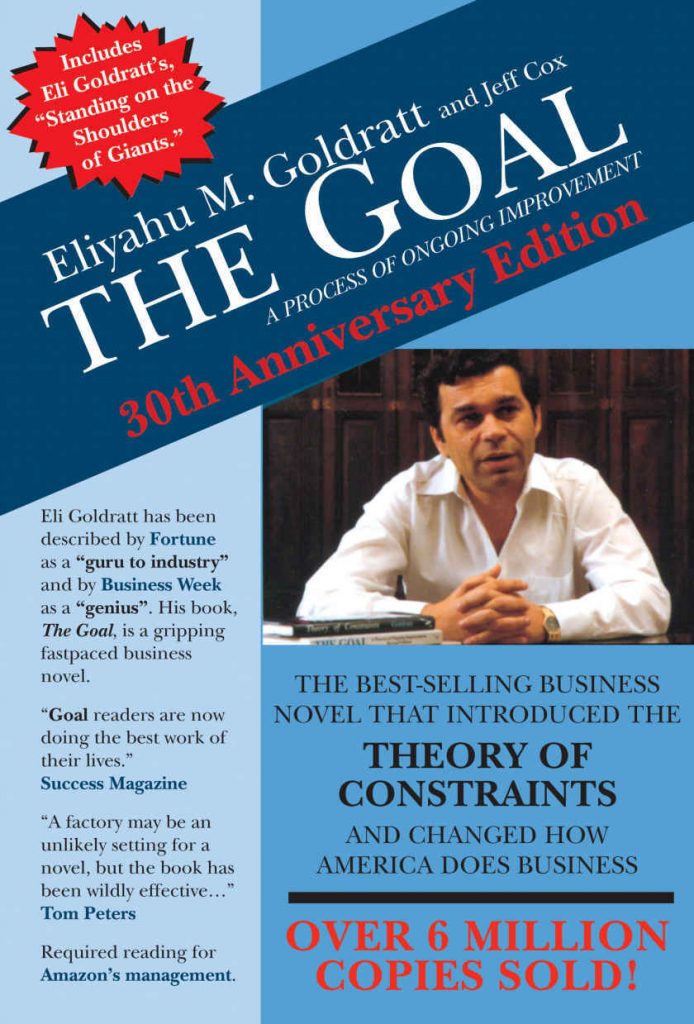

Times have changed since the 1980s, but operations fundamentals have not. The timeless challenges of productivity and workplace structure mean new generations return to and learn from the same well that is The Goal by Eliyahu Goldratt and Jeff Cox (384 pages, 1984).

The Goal, subtitled A Process of Ongoing Improvement, uses two rhetorical techniques to inform and persuade the reader: (1) an appealing fictional account and (2) the Socratic method. The characters engage in a seductively innocent dialogue—akin to Ishmael, the 1995 blockbuster novel by Daniel Quinn—and the characters’ personal challenges make them relatable.

Alex Rogo, the protagonist, urgently wants to keep his manufacturing plant alive, so he applies operations ideas gleaned from brief interludes with a physics professor, Jonah. As Alex Rogo finds success, the natural inference is that Jonah’s wisdom carries weight. Further, the dialogue between Alex Rogo, his wife, and his work peers suggests Jonah’s ideas are common sense, for anyone who is attentive and willing to think logically.

So why does that not happen? Why is there so much inefficiency that goes unchecked?

Aside from human irrationality, the title itself points to the main shortcoming: the lack of a clear goal. In the pursuit of vague excellence—or mere survival—firm managers often fail to examine what comprises success and whether their actions align.

Elucidating one’s goal, however, is far from the end of the story. Making it happen is another matter altogether. The Goal contains a mountain of tidbits and epiphanies, but once the dust has settled and the numbers are forgotten, four key insights remain.

1. Common Practice Is Not Common Sense

Perhaps the most recurring line (paraphrased) in the novel is “that is the way we do it” or “that is the way everyone does it.” Even when Alex Rogo is having marriage struggles this comes up. He wonders why he is married, and his exasperated wife says “it’s just what people do!”

Goldratt and Cox challenge the reader’s status-quo bias. The fact that a process is the incumbent, especially amid glaring problems, is at best a hollow argument. Likewise, argumentum ad populum—an appeal to popularity—is a fallacy of logic.

2. Measure What Matters

We live in a data-rich world and can be easily sidetracked chasing the “best” in arbitrary metrics. As documented by David Boyle in The Sum of Our Discontent: Why Numbers Make Us Irrational (200 pages, 2001), much of the data in the popular press is inaccurate and misleading.

Goldratt demonstrates misaligned metrics through Alex Rogo’s realization that factory robots are not improving plant profitability, only local efficiency. Worse, to inflate robot efficiency, workers run them unnecessarily and stockpile inventory. “We’ve been building parts we don’t need,” Rogo winces.

In desperation, Alex Rogo manipulates his reports because the correct numbers would divert his plans and bring his bosses down on him. The statistician protests, but subsequent profitability vindicates Rogo and highlights the irrelevance of the reported numbers.

Data can allow firms to objectively examine performance and pinpoint vulnerabilities. However, the wrong targets misdirect attention and fail to contribute towards the goal. Ideally, metrics (1) reflect progress towards the goal and (2) provide a tangible basis for improving operations.

3. Go to War with Constraints

The organization devoted to preserving and disseminating Goldratt’s legacy is aptly called the Theory of Constraints Institute. In fact, The Goal concludes with five focusing steps, all of which elevate constraints, AKA bottlenecks, as pivotal to productivity.

Counterintuitively, this does not mean using every resource at its full capacity. Alex Rogo finds an analogy during a hike with his son’s Boy Scouts troop. Rogo realizes no scout can go faster than the boy in front of him, no matter how fast the scout is. Back at the plant, optimizing non-bottleneck resources does not increase overall productivity, rather it increases inventory and operational expenses.

In Goldratt’s words, to raise global productivity, “subordinate everything to the constraint,” since it is a ceiling on improvements.

4. Results Are Not Enough

As organizations expand, they acquire rent seekers: those who profit from the status quo on account of their positions rather than their productivity or merit. To keep the gravy train rolling, rent seekers have an incentive to fight reform and innovation, even if they are an unequivocal benefit to the bottom line.

An example from The Goal is the union that stands in the way of layoffs and process improvements that would require workers to take on new or different roles. This is closely related to the status-quo bias, and it means a change agent must engage in persuasion and corporate politics, to advocate for the best approach to operations. No matter how logical or smart a plan is, it is likely to encounter resistance.

Lessons in The Goal extend far beyond traditional manufacturing. Medical care, for example, suffers from many of the issues Goldratt wrote about. Hospitals quote value-based care (increased quality and lower costs) as the overarching goal but lack accepted metrics. Administrators wade through data that spurs local changes but not quality or cost improvements.

For managers, The Goal helps align actions with outcomes. Beyond the take-home lessons, though, Goldratt and Cox pioneered the operations novel, a genre that has come of age, including Epiphanized (414 pages, 2015) by Bob Sproull and Bruce Nelson. People think and learn in words and stories, rather than formulas, so the theory of constraints in an entertaining novel commands an audience far wider than it would in a conventional textbook. The audio version makes this story even more convenient and entertaining, especially with the comical, cartoonish voices for different characters.