On September 19, the China Development Institute and venture firm Z/Yen Partners released the 26th edition of the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI). Known as a leading guidebook for investors, it evaluates the competitiveness of 104 financial hubs around the world. For the first time, Santiago de Chile appeared on the index.

The Chilean government celebrated this as the first step in its plan to turn the capital city into a leading financial center in Latin America. During Chile Day on September 10 in London, Finance Minister Felipe Larraín announced 10 key measures to make this happen.

Content

- Harnessing Economic Stability

- The Plan: Regulatory Overhaul

- Focus on Fintech

- Expected Results

- The Challenges

On September 19, the China Development Institute and venture firm Z/Yen Partners released the 26th edition of the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI). Known as a leading guidebook for investors, it evaluates the competitiveness of 104 financial hubs around the world. For the first time, Santiago de Chile appeared on the index.

The Chilean government celebrated this as the first step in its plan to turn the capital city into a leading financial center in Latin America. During Chile Day on September 10 in London, Finance Minister Felipe Larraín announced 10 key measures to make this happen.

Harnessing Economic Stability

Chile is the richest nation in South America with a GDP per capita of US$25,222 and exhibits one of the freest economies in the world. While her $8.24 billion in foreign direct investment is lower than that of neighbors, Chile is one of the most attractive Latin-American countries for doing business. She is a party to several free-trade agreements and her GDP growth in 2018 was 4 percent, above the regional average.

According to Fitch Solutions, Chile is the most stable country in Latin America in terms of political, economic, and operational risks. The nation’s performance has improved over the last years in part due to Sebastián Piñera’s election and his administration’s focus on business-friendly policies.

Chile’s 2019 Risk Score by Fitch Solutions

(100=stable; 0=unstable)

| Country Risk Index | 70.5 |

| Operational Risk Index | 64.1 |

| Long-Term Political Risk Index | 83.2 |

| Short-Term Political Risk Index | 74.8 |

| Long-Term Economic Risk Index | 66.3 |

| Short-Term Economic Risk Index | 70.6 |

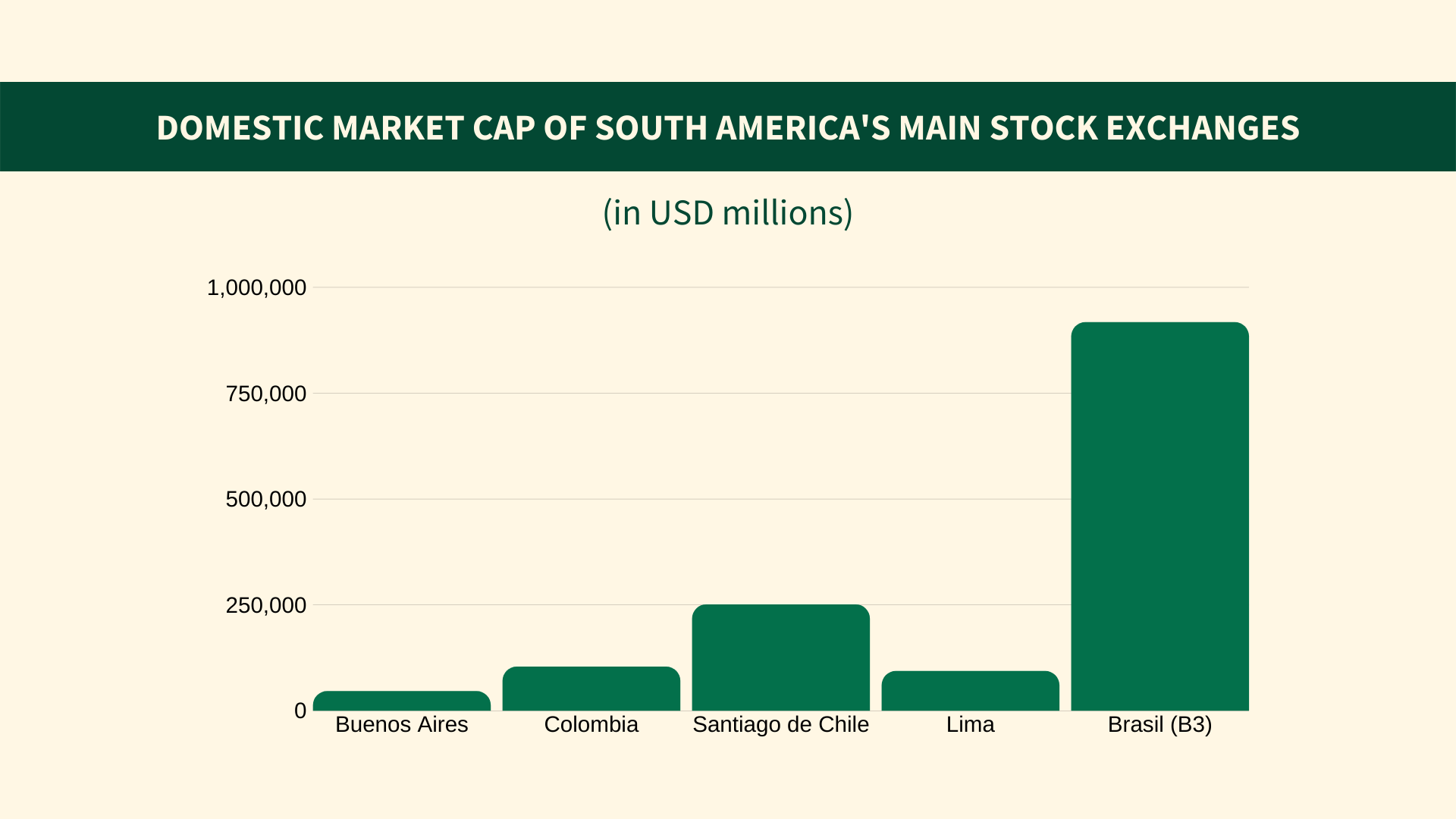

Nevertheless, Chile has a lot to catch up when it comes to financial markets. Over the last 12 months, Chile traded on average $154 million per day in stocks, while Brazil traded $4 billion. Hong Kong, a world leader, traded $9.6 billion. The GFCI ranked Santiago as the 99th financial center in the world, the last in the region behind Rio de Janeiro (87), Panama (86), Sao Paulo (82), Buenos Aires (80), and Mexico City (62).

Source: The World Bank

Chile has three stock exchanges: two in Santiago and one in Valparaíso. The Santiago Stock Exchange (SSE), founded in 1893, concentrates the most transactions and is among the largest in Latin America by market capitalization. SSE is part of MILA, a regional stock exchange that integrates the capital markets of Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Peru.

The Plan: Regulatory Overhaul

In London, the Finance minister unveiled the plan, which includes a bill with 10 measures and reforms to 11 existing laws. It builds upon the experience of countries that became magnets for capital markets such as Hong Kong and Singapore. The main areas are:

- Adopting international best practices and rules

- Lowering entry barriers for foreigners to list securities and trade fixed-income assets

- Streamlining financial legislation

- Speeding up the process of bond-issuing

- Harmonizing the tax system for local and foreign investors

- Incentivizing capital markets with friendlier regulations

- Removing investment caps on institutional investors

Focus on Fintech

The Chilean fintech industry is experiencing steady growth. According to Finnovista, a startup incubator and accelerator in Latin America and Spain, the fintech ecosystem in Chile grew by 49 percent from December 2017 to June 2019. The areas with most activity are payments and remittances—including cryptocurrency—, enterprise and personal financial management, technologies for financial institutions, and crowdfunding.

The government is aware of this trend. On April 15, Larraín announced a bill to regulate cryptocurrencies and fintech services. His goal is to have a basic legal framework that is flexible enough to not hinder progress but that eliminates regulatory uncertainty regarding startups with innovative business models.

According to Chile’s financial officials Mario Farren and Joaquín Cortez, the bill will be ready before the end of 2019 and will enter Congress along with another bill to regulate new insurance services, which is another industry that fintech startups are disrupting.

Expected Results

Larraín has acknowledged that this ambition is not new. Previous administrations have tried without success to make Chile a leading financial center. However, he argued that regulatory reforms do make a difference. For instance, a 2014 reform increased Chile’s investment funds’ total assets from $10 billion to more than $25 billion.

The plan involves several institutions, not just lawmakers and regulators. The central bank, for instance, is rolling out several policies to strengthen and modernize the monetary system. According to Larraín, if the efforts bear fruit, employment in the financial industry could triple over the next years.

The Challenges

Claudio Parés, head of the Economics department at Universidad de Concepción, celebrated the idea of making the Chilean financial markets more competitive on the world stage. However, he is less optimistic about the purported economic returns.

“Financial centers should rely on concrete, real, and tangible economic activities. Otherwise, all they do is redistribute wealth,” he told local newspaper Concepción. “It is not a labor-intensive industry.”