Judging by the vast number of publications on Nazism, one would think that there is little left to uncover. A new book from Paraguay, once a hideout for WWII fugitives in the heart of South America, suggests there are many stones unturned, including lessons for today’s politics.

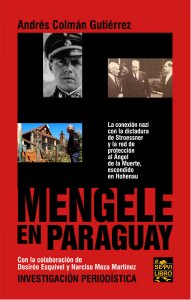

Mengele in Paraguay (Servilibro, 2018) by veteran journalist Andrés Colmán Gutiérrez, co-authored with Desirée Esquivel and Narciso Meza, is a rare feat in a country with an unfortunate lack of long-form investigative journalism. A short DVD documentary featuring unseen footage and interviews accompanies the book.

The 330-page volume, which includes unpublished photos and documents, tells the gripping story of Josef Mengele—known as the “Angel of Death” for his barbaric medical experiments on Auschwitz prisoners—once he fled postwar Germany. It’s also a powerful broader indictment on South American governments that at the time harbored and even actively protected war criminals. Argentina was the favorite haven for fleeing Nazis under the rule of Juan Domingo Perón, a polarizing hero of left-wing parties and causes to this day. Chile, Bolivia, and Brazil also provided shelter to high-ranking officials.

Alas, Mengele was not the starting point for Paraguay’s history with anti-Semitism. Bernard Förster, an early nationalist ideologue who married Friedrich Nietzsche’s sister Elizabeth, attempted to create a racially pure colony in 1886 along with 14 German migrant families. “New Germany” in Paraguay failed disastrously, but the seeds were planted. The first Nazi Party outside Germany was founded in Paraguay no less, in 1927. When Hitler came to power, German schools in Paraguay taught Nazi doctrine, and youth groups held parades in support of the Third Reich. The Paraguayan government backed the Axis Powers at the onset of WWII, and only switched sides at the last minute as the outcome became clear.

Therefore, by the time Mengele traveled to the country for the first time in 1951 to explore business opportunities, Nazism as a political movement was already well established. Most German immigrants in South America abandoned Nazism after the Holocaust’s horrors surfaced, but some remained loyal and set up a covert network to hide fugitives coming from Europe. In 1954, the longest military dictatorship in South America began: General Alfredo Stroessner, himself of German descent, would hold onto power for the next 35 years. Hans Rudel, the famous Luftwaffe pilot and outspoken Nazi activist, was a close friend of the Paraguayan ruler.

It was this environment that attracted Mengele, who, thought dead, was able to evade the trials that judged other concentration-camp physicians. He had been living in Buenos Aires, Argentina, since 1949, selling agricultural machinery through a family firm subsidiary. Two changes forced him to move to Paraguay in late 1958: the fall of President Perón three years earlier and the Jewish Nazi hunters who had discovered he was still alive and were following his tracks.

So easy was the move for Mengele that the Supreme Court granted him Paraguayan citizenship a few months later under his real name with fabricated testimonies. Thanks to it, Mengele was able to spend over a year unbothered at a local leader’s ranch in Hohenau. Local police duly ignored an extradition request from the German justice ministry that arrived shortly thereafter. Diplomatic requests fell on deaf ears.

The authors’ additions to the Mengele story come at this point. For the first time, someone who lived with the Nazi officer during that time agreed to go on the record and show the small house they shared. A dozen new interviews shed light on the man’s rather uneventful stay and the dynamics of the self-imposed “pact of silence” that, out of fear, prevented townspeople from talking. There was even a concentration-camp survivor who traveled all the way from Auschwitz to Asunción to start a new life—only to revive the nightmare as she stumbled upon her Nazi jailer in a family jewelry store.

Mengele left Paraguay when news from Argentina arrived that an Israeli secret commando had abducted another top Nazi official, Adolf Eichmann. Correctly thinking he was next, as evidenced by unclassified documents and Mossad testimonies, he fled to Brazil around 1960, where he ultimately drowned in the sea many years later. He never faced justice.

Given the conspiracy theories that still exist around Nazi presence in South America, including one that Adolf Hitler himself is buried somewhere inside a hotel in Paraguay, the well-documented book is important because it sets the record straight and corrects many speculations by previous researchers. It also suggests there were many lesser known WWII fugitives who successfully evaded justice, such as the Croatian Ustaches, who worked as spies for the Paraguayan regime.

The publication is also timely. Paraguay’s outgoing president, Horacio Cartes, is involved in a scandal relating to a fugitive he protected much like Stroessner did with Mengele. Darío Messer—a Jewish businessman long sought by the Brazilian justice ministry for money laundering and whom Cartes once described as his “soul brother”—moved to Paraguay around 2011. Likewise, he received Paraguayan citizenship from friendly Supreme Court justices and even took part in an official state visit to Israel. When police came looking for Messer after an extradition request arrived this year, someone tipped him off and he went into hiding. He remains at large.

“Those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it” is an often repeated and misattributed phrase. What the saying doesn’t mention, though, is the wide gap between knowledge and will. South America’s reputation as a hideout for criminals will persist as long as its governments are unwilling to take the rule of law seriously. A region so desperate for transparency, investment, and less corruption cannot afford a new Mengele or Darío Messer.