The International Property Rights Alliance, along with 113 think tanks throughout the world, released the 12th edition of the International Property Rights Index (2018 IPRI) on August 8. The index shows that global property rights have improved for four years in a row, albeit at a slow pace. Still, over half of the world’s population remain without adequate property-rights protection.

The average global score increased by 1.95 percent, to 5.74 out of a maximum score of 10. While countries such as Cyprus, Latvia, and Israel have shown considerable property-rights improvement, nations in the Americas have made little progress.

The report’s main author is Sary Levy-Carciente, a Venezuelan economics professor and member of the free-market think tank CEDICE.

The 2018 IPRI gathers data from several databases from 125 countries—accounting for 98 percent of world GDP and 93 percent of the global population—and converts several indicators into a scale from zero to 10. Then it determines three key components of the property-rights ecosystem: legal and political environment, physical property rights, and intellectual property rights.

Low income countries saw the biggest decrease in IPRI Scores this year #IPRI2018 https://t.co/lAFY5WgrQt pic.twitter.com/IBIebpYR1o

— PRA (@PRAlliance) August 10, 2018

Finland, New Zealand, and Switzerland head the list this year, with Finland switching places with New Zealand and becoming the leader in the intellectual-property-rights component. Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Australia, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Canada complete the top-10 list.

Property Rights in the Americas

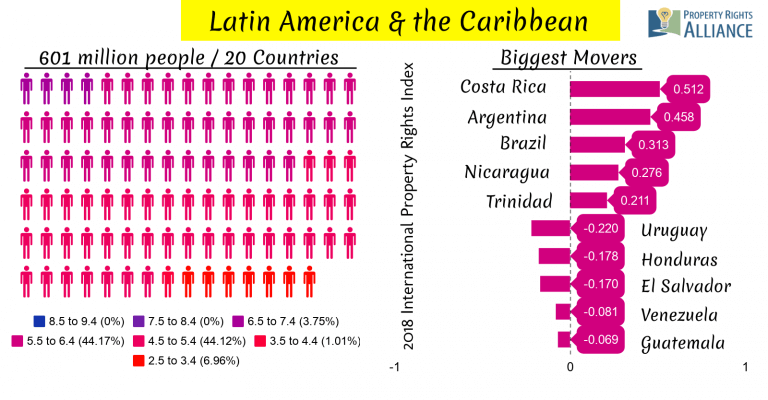

There is no surprise in the Americas, with Latin-American nations falling behind in the ranking.

Canada and the United States are the regional leaders and have shown a slight increase in their general scores from the previous year. They occupy the 10th and 12th places of the global index, respectively. The US scores show a minor decrease in her legal and political environment. However minimal, this component is what ultimately sets top countries apart from the rest, according to the report. Moreover, Finland dethroned the United States in the intellectual property rights ranking.

Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay come next in the regional ranking. They rank 29th, 31st, and 43th globally, which is consistent with other indexes that show that these countries have better economic and political institutions than the rest of Latin America. Nevertheless, Chile’s and Uruguay’s property-rights performance decreased this year.

Brazil and Mexico, the most populated Latin-American countries, stand at the 55th and 72nd places, respectively. While Brazil improved her scores in all three components, Mexico showed a poor performance in each.

Colombia and Argentina rank 61st and 79th. Both countries have increased their scores from the previous year, although Argentina has been experiencing high inflation rates, which devalue property and decrease the currency’s purchasing power.

Unsurprisingly, given their current political and economic crises, Haiti and Venezuela are at the very bottom of the list. The index incorporated Haiti this year only to give her the bad news that she is the worst-rated country regarding property-rights protection. Venezuela, once a Latin-American economic leader, has not achieved a score higher than 3.5 during the whole IPRI history.

Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, who has conducted extensive research on property rights around the world and co-authored previous IPRI editions, highlighted an interesting case study. Georgia is implementing blockchain technology to register property titles. In part thanks to this innovation, Georgia received a perfect 10 score in the property-register subcomponent.

“It is an example of how technology can enable countries, even from the former Soviet Union, one of the weakest regions in the world in terms of property rights, to leapfrog over the best,” he said.

The report also analyzes correlations between IPRI scores and other rankings such as Global Entrepreneurship, Human Freedom, World Electoral Freedom, Corruption Perceptions, Network Readiness, and more. This quantitative analysis mainly demonstrates that stronger property-right environments lead to more entrepreneurship and productivity, stronger political institutions, less corruption, and higher civic engagement through the internet.

These results bolster the statement from Levy-Carciente on property rights: “It is a catalyst for growth and a catalyst for development. Development is not just economic growth; it’s a very complex and multidimensional concept.”

Indigenous Rights, Gender Inequality, the Austrian School

Every year, the IPRI report includes select case studies that document the development of property rights around the world. In this edition, the studies portray indigenous efforts to strengthen the property-rights environment in Ukraine, Malaysia, Nepal, and South Africa. Another study narrates Japan’s accomplishments through the legal and political evolution toward a liberal democracy after World War II.

A new addition to the 2018 IPRI is a study that explores the understanding of property rights from a particular school of economics. The author is Barbara Kolm, who develops an analysis from the Austrian perspective.

The 2018 IPRI also explores gender inequality in property rights, since the Property Rights Alliance believes full access to them is a basic human right. The report found out that Latin-American countries enjoy far higher gender equality than those in the Middle East and North Africa.

The report merits deeper analysis, but Levy-Carciente’s conclusion at the launch event in South Africa is a well-rounded summary. The 2018 IPRI scores, coupled with additional data from other indexes and the case studies, suggest that “high-income and high-development levels indicate there is a positive correlation between a property-rights regime and well-being.”