I have a hard time getting enthusiastic about International Women’s Day, since I do not agree with most causes that it appears to advocate for nowadays, such as gender vindication.

In an attempt to liberate women from historical and cultural oppression, the most vocal activists demand all sorts of privileges and regulations. Research has shown, however, that enacting differential provisions for women in the labor market actually reduces their opportunities and increases discrimination.

I wholeheartedly agree that women should have equal access to opportunities, but I do not believe that extensive normative frameworks and numerous coercive measures will help women attain them. Instead, women should strive to be equal before the law and free from both male and governmental rule.

Rosemarie Fike buttresses this perspective with her recent research for the Fraser Institute: “Women and Progress: Impact of Economic Freedom and Women’s Well-Being.” She explains that clear legal rules, which allow women to make their own economic decisions, are precisely the way forward to achieve wider opportunities for women.

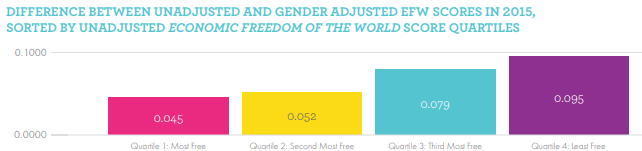

In her analysis, she first integrates the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index with a new Gender Disparity Index to observe how the scores of the 159 countries change by the gender adjustment.

A major finding is that countries with the lowest levels of gender disparity are also the most economically free countries. Those nations in the least free quartile show, instead, larger average differences between gender-adjusted and non-adjusted scores.

Fike then incorporates relevant economic and social metrics to examine the level of outcomes for women in each nation. She addresses four particular areas: economic and labor markets, health, education, and financial independence.

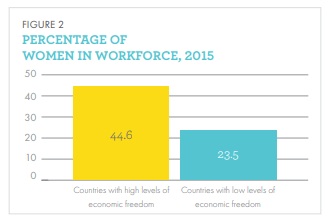

The results demonstrate that women living in the nations with high levels of economic freedom have improved their living conditions markedly since 1970, at least in terms of employment: “Women are almost twice as likely to participate in the [labor] market” in these countries.

Further, fewer than 15 percent of women work in vulnerable conditions in economically free countries compared to the almost 40 percent rate in countries with low economic freedom. Women enjoying economic freedom live an average of 17 years more, and 94 percent of them can read—which is 34 percent more than in the other nations.

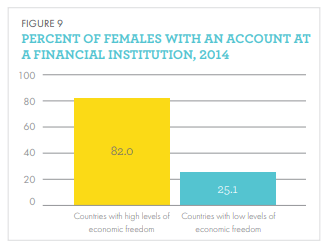

Having a bank account is a hallmark of financial independence, which unfortunately only 25 percent of women enjoy in countries with low levels of economic freedom, compared to 82 percent of women in economically free countries.

This study suggests that a tried-and-true, highly effective way of expanding women’s opportunities is encouraging equal access to institutions that promote economic freedom. In the same vein, we should make sure that women have the legal autonomy to make their own economic decisions.

The way to empower women is providing them with tools to pursue their own happiness as they so define it. No civil servant or feminist-movement leader has the authority to determine what success means for women.

The conversation needs to shift away from comparing end results for men and women, which are and will continue to be different. Instead, civil society and policymakers should focus on removing the barriers women face toward economic and political freedom.

That way, women will achieve progress and well-being in their own way, on their own merits, without the need for feel-good, counterproductive handouts.

This article was first published by AIER.