Although China and the European Union compete at close quarters with the United States for international-trade leadership, the latter has an ace up her sleeve: the world’s second highest de minimis thresholds (DMT), a little-known variable that greatly facilitates electronic commerce and retail sales.

DMT is the amount below which a country imposes no duties, taxes, and other customs procedures on traded goods. Shipments valued above the DMT must endure costly and time-consuming regulations. Therefore, a lower DMT ensnares more goods in red tape, while a higher one lets trade flow more freely.

Having a high DMT not only benefits businesses and consumers, it even helps governments save money, as Christine McDaniel, senior research fellow at Mercatus Center, demonstrates in her analysis A Trivial Legal Issue with Nontrivial Economic Consequences.

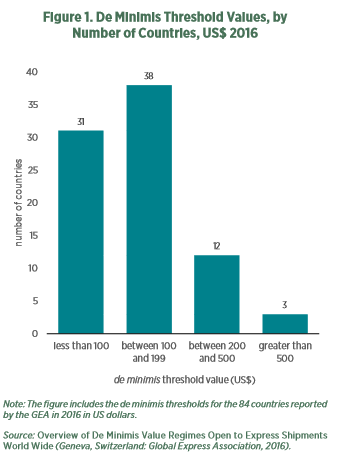

The US government is already eliminating waste after raising its DMT from $200 to $800 in March 2016, after the passage of the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act. Only Qatar surpasses the United States, with a threshold of $822, and just 15 countries meet the International Chamber of Commerce’s recommendation “of a global baseline de minimis value of at least $200.”

She argues that international trade and e-commerce would significantly speed up and increase if other countries followed the lead of the United States and raised their own DMTs. Small and remote businesses would be the main beneficiaries of these reforms, since barriers preventing them from participating in the global marketplace would go down.

Consumers, in turn, would enjoy lower prices and governments would incur lower administrative costs, after freeing up a substantial share of goods from customs procedures. For that reason, McDaniel stresses the importance of including higher DMTs in the ongoing NAFTA renegotiaton, as well as for future WTO programs and free-trade agreements.

Even though the United States now profits from a more cost-effective and swifter customs system, it is still a concern when the DMT of its major commercial partners remain low. For instance, Canada’s threshold is just $16 (CAN$20), which burdens US businesses when exporting almost any product to their neighbors.

Of course, this is even worse for Canada. The Canadian government spends $38 to $48 per parcel on customs formalities—all that just to collect an average of $2.90 on duties and taxes.

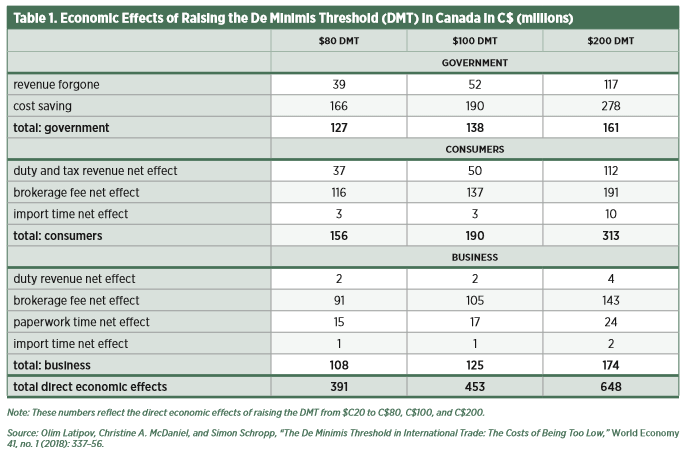

In another study by McDaniel, The De Minimis Threshold in International Trade: The Costs of Being Too Low, coauthored with Olim Latipov and Simon Schropp, she examines what Canada has to gain by increasing the DMT to $80, $100, and $200.

Canada could save $300 million annually with a DMT of $80 and up to $513 million with a threshold of $200, as published in The World Economy journal.

It’s not hard to see how higher thresholds would lead to even greater gains, as governments spend fewer taxpayer dollars on inefficient customs formalities that entail delays and increases in final prices. Furthermore, removing e-commerce’s barriers to global trade would provide the opportunity for more sensible regulation instead of numerous taxes and tariffs.

Commerce is just another manifestation of people’s desire to exchange with one another and improve their lives. For that reason alone, expanding international trade and allowing small businesses to flourish is not just a more efficient allocation of resources, it’s a moral imperative for open and democratic societies.

This article was first published by AIER.