By Melinda McCrady

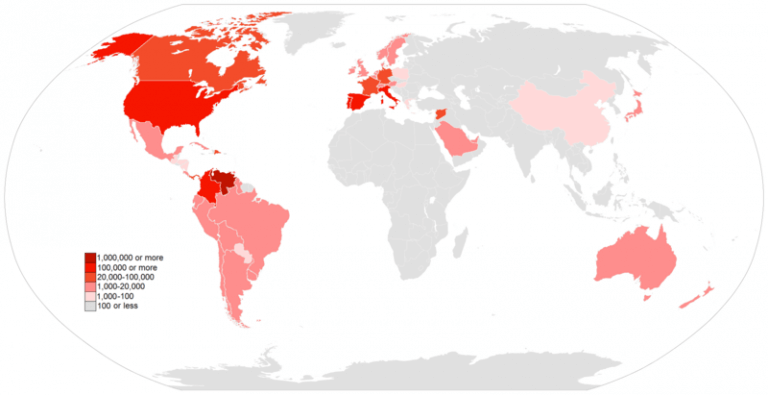

Venezuelans are fleeing the country’s economic and political crisis for a better life, creating a diaspora that spans the globe. While most go elsewhere in Latin America, those with the right ancestry escape with citizenship by descent, usually to Europe.

One such man is Dakar Parada of Caracas, who plans to never return. His grandparents came from Spain, and he left Venezuela in 2007, just as the situation was snowballing downhill under the reign of the late Hugo Chávez. Parada found work as a computer programmer and studied for a master’s degree in Austrian economics at Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid.

The field of studies opened his eyes to libertarian ideas, and Parada soon realized the bleakness of the situation back home. He found explanations for the hyperinflation, crime, political instability, and economic crisis, and he began blogging his insights.

What is the key lesson from Venezuela’s failure?

“There’s no question about it,” he says. “Venezuela has socialism.”

He takes particular exception with this point, because “on countless occasions [he has] read or heard different outlets affirm that Venezuela is not socialist or that Venezuela is not communist.”

He points directly to the Communist Manifesto and notes the nationalization of the petroleum industry, confiscation of private industries, and an array of monopolized sectors in state hands. Further, by way of comparison to other nations, Venezuela has one of the lowest scores for economic freedom in the world, according to the Heritage Foundation, right between Zimbabwe and Cuba.

People should remember, he adds, that the political opposition are socialist as well. That is why they refer to the Chavista regime as a dictatorship or a criminal government, but they fail to highlight its socialist policies, aided by advisors from totalitarian Cuba.

“The consequences are evident, the decrease in the quality of life of the people, the impossibility of saving money, and the impossibility starting a company.”

Spain may have a shared language and cultural similarities, along with many Venezuelan expat communities. However, Parada eventually continued on to Ireland for his career in IT, which required a greater cultural adjustment.

There are only a handful of Venezuelans in Dublin, but he has integrated into the broader Hispanic community, and even picked up a side-gig as a salsa instructor. Still, “You’re missing your friends, you’re missing your food.… I think the thing I miss the most is the weather.”

Regardless of the pain of homesickness and separation from family, he hopes “never to return to Venezuela.”

“I am trying to convince my mom to come.” However, he recognizes that she has a greater challenge, being older and more ingrained in Venezuelan society.

The one flicker of hope Parada sees is the growth of a classical-liberal movement in Venezuela. They have a small yet growing following, as they promote free-market ideas, including anarcho-capitalism. Also, for the first time in recent history, libertarians in Venezuela have formed a political party that furthers the ideas of liberty.

For now, Parada must remain content that his contact with other Venezuelans happens mostly online. Such friends now span the globe, from Australia to Abu Dhabi: “Every one of them misses a little bit of Venezuela.”

Guest author

Melinda McCrady holds a Bachelor of Arts in journalism from California State University, Long Beach, where she also worked as a webmaster for various organizations.

Fergus Hodgson contributed to this article.