For over a decade, the US government has enacted sanctions against Venezuelan individuals linked to terrorism, drug trafficking, and other criminal activities.

But it wasn’t until 2015 that a sanction specifically addressed the Nicolás Maduro regime’s longtime assaults against democracy and human rights.

Content

- How many Venezuelan officials are subject to US sanctions?

- Timeline of key sanctions against the Venezuelan regime

- Why is Nicolás Maduro still in office?

- US Sanctions on Venezuelan versus oil-production losses

.

.

How many Venezuelan officials are currently subject to US sanctions?

The US Treasury Department currently sanctions 88 individuals and 46 entities from, or related to, Venezuela. The State Department has revoked the visas of hundreds of Venezuelans for several reasons.

.

.

Timeline of key sanctions against the Venezuelan regime:

December 2014: The US Congress passed the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act, which required the president to impose sanctions on officials who repressed the February 2014 student-led protests across Venezuela.

March 2015: President Barack Obama issued an executive order implementing the 2014 act by freezing assets and revoking the visas of seven Venezuelan officials: six members of the Venezuelan security forces and a prosecutor.

July 2015: The US Treasury Department codified the Venezuela sanctions into the Code of Federal Regulations (31 C.F.R. Part 591).

July 2016: The US Congress extended the 2014 act through 2019 in the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Extension Act of 2016.

May 2017: The US Treasury Department added eight names to the list of sanctioned Venezuelan officials: the president of the Supreme Court and seven justices.

August 2017: President Donald Trump issued an executive order prohibiting US citizens, companies, and anyone financially related to this nation from purchasing or trading new Venezuelan government debt with a certain maturity, including the state-owned oil company PDVSA bonds.

March 2018: Trump signed another executive order prohibiting transactions involving the petro, a Venezuelan state-backed digital currency Maduro launched in 2018 to circumvent international financial sanctions.

May 2018: The day after Maduro’s illegitimate reelection, a new executive order effectively cut off the Venezuelan government, including PDVSA, from any kind of debt financing, limiting the Maduro regime’s ability to raise funds.

September 2018: The US government extended sanctions to key Maduro loyalists, including his wife Cilia Flores, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, Defense Minister Padrino López, and Communications Minister Jorge Rodríguez. In addition, it froze assets and sanctioned individuals linked to ruling-party chieftain Diosdado Cabello.

November 2018: President Trump issued an executive order that allows the asset blocking of, and banning certain transactions with, any person operating in the Venezuelan gold sector or linked to government corruption.

January 2019: The United States sanctioned several individuals and firms involved in a corruption scheme to profit from Venezuela’s currency controls, including a TV executive. Another Trump executive order extended sanctions against PDVSA, freezing its assets in the United States and banning US persons from trading with it.

March 2019: Venezuela’s state mining company joined the list of US sanctions. In addition, the US State Department released a statement warning oil traders against Venezuela purchases: ”You should not be buying oil from this regime… we have a wide broad net with sanctions… be careful not to get caught in that net by activities you may think don’t come into it but actually are caught by it.”

April 2019: The US Treasury froze the assets of firms that traded Venezuelan oil for Cuba, of shipping companies with Venezuela ties, and of the country’s central bank. The Office of Foreign Assets Control ”identified nine vessels, some of which transported oil from Venezuela to Cuba, as blocked property owned by the four companies.”

May 2019: After a failed uprising against Maduro, the Treasury Department lifted sanctions on a former general who had defected from the regime. It also designated two shipping companies and two ships as targets for transporting Venezuelan oil to Cuba.

.

.

Why is Nicolás Maduro still in office?

Even though the sanctions have restricted Maduro’s ability to finance his regime through US capital markets, the Venezuelan ruling class has broad control over the underground economy, which generates billions in drug trafficking, illegal mining, and contraband. Moreover, as millions of Venezuelans flee, the government has to devote less funding to public services.

Remittances are another factor that keeps the Venezuelan society from collapsing. Caracas-based consultancy Econoanalítica estimates the flow of remittances into Venezuela will surpass $4 billion in 2019. Given the hyperinflation of the country’s currency, even monthly transfers of $20 can help Venezuelan families to survive.

”Venezuela has essentially stopped exporting oil and in its place, started exporting people,” Bloomberg columnist Andrew Rossati noted.

.

.

US sanctions on Venezuelan versus oil-production losses

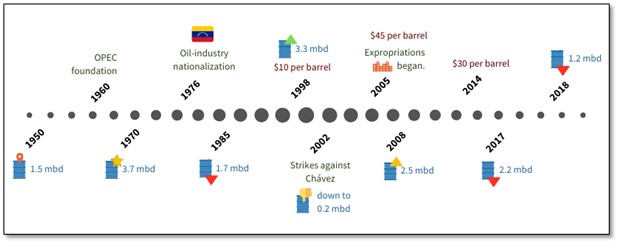

Venezuela’s oil production plummeted by millions of barrels prior to US-imposed economic sanctions against PDVSA.

Keith Johnson, Foreign Policy‘s global economics correspondent, argues the decline of the Venezuelan oil industry can be traced back to its nationalization in 1976. Encouraged by the boost in government revenue, then President Carlos Andrés Pérez extended state intervention into the economy to accelerate development.

Sources: Johnson, K. (2018) How Venezuela Struck It Poor. Foreign Policy.; Giordani, J. (2006) Venezuelan Oil Figures. Voltaire Net.

Just one decade later, global oil prices dropped, and Venezuela suffered the consequences of her reliance on oil exports. According to 2017 data from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), oil accounts for 98 percent of the country’s export revenues.

In 1998, the price of oil collapsed to about $10 per barrel, shattering the Venezuelan economy and politics, setting the ground for Hugo Chávez’s rise to power. A decade later, with oil peaking at $150 per barrel, the Chavista regime was able to bankroll a generous welfare state.

In 2001 and 2002, Chávez gave PDVSA a monopoly on all new oil exploration and production and forced foreign firms to become minority shareholders in any partnership with the state-run firm. By the end of the second year, after the first national strike against the government, Venezuela’s oil production decreased from 3 million barrels per day to 2.6 million.

From 2005, Chávez expropriated assets from private oil companies operating in Venezuela. By 2008, oil production had dropped to 2.5 million barrels per day.

Patrick Duddy, US ambassador in Caracas from 2007 to 2010 (with an eight-month interruption), told Foreign Policy that ”In 2007, there were already intermittent shortages… no milk of any sort on the store shelves, not fresh, not powdered, not condensed—and this was when oil prices were soaring. It was startling.”

The economic crisis worsened in the summer of 2014, when oil prices fell to $30 per barrel by the end of 2015, half of what was necessary to sustain Venezuela’s government budget. The Venezuelan GDP subsequently shrank by 6 percent that year.

In 2017, Venezuela’s oil output declined further to 2 million barrels per day and continued to drop to 1.1 million barrels per day by the end of 2018. The latest OPEC numbers show that the country’s oil production plummeted to just 732,000 barrels per day in March 2019, making Venezuela the world’s tenth oil producer despite having the largest proven reserves.

Previous Coverage

- “Venezuela’s Rightful President Needs White House Support,” Epoch Times, by Fergus Hodgson.

- “Venezuelan Regime Deploys Cryptocurrency to Evade US Sanctions,” Epoch Times, by Fergus Hodgson.

- “Six Takeaways from Venezuela’s Dystopia,” Frontier Centre, by Fergus Hodgson