By 1988, Augusto Pinochet had ruled Chile for more than a decade, and the international community pressured the general to legitimize his position democratically with a plebiscite. Every night for one month prior, the campaigns for his continuation (“yes”) and his rejection (“no”) had 15 minutes on national television to make their arguments.

The documentary film, No (2012), captures this historic moment for Chile and Latin America through the eyes of the “no” campaign. It shows the strategy that successfully emboldened the people and brought down the dictatorship.

Members of the “no” campaign sought to generate widespread understanding of the negative consequences of the dictatorship, and thus motivate the population to participate in the plebiscite and vote against Pinochet. However, the campaign’s advertising chief, René Saavedra, was concerned that invoking 10 years of pain would not motivate people. They already feared the regime, and such an emphasis would make them remember why.

The film, recorded with cinema techniques from the 1980s, demonstrates how a political campaign succeeds if it appeals to the emotions, to common desires such as peace and vitality. Saavedra had to get people to watch television when they would normally go to sleep, convince opposition leaders to focus on the positive, and finally, to win the referendum.

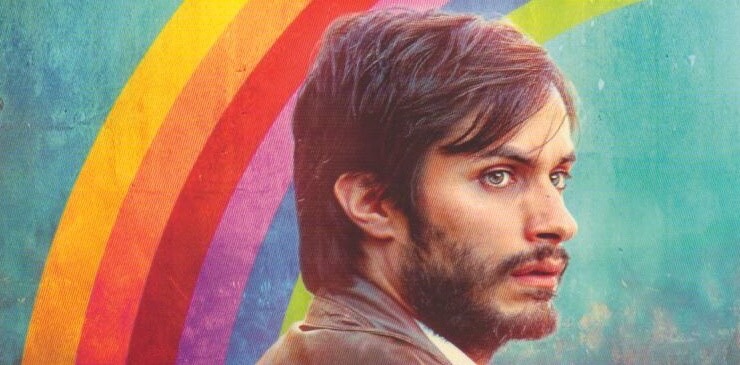

He proposed a rainbow as the logo, to symbolize calm after the storm. In addition, each color of the rainbow represented one political party, and the rainbow as a whole represented the coalition. The slogan for the campaign was “Chile, ¡la alegría ya viene!” (Chile, happiness is on the way), and it was part of the lyrics to an accompanying jingle.

Saavedra’s strategy garnered unexpected success, and Pinochet’s allies were so concerned that they sought to counter his clips with advertisements right afterwards. As each day passed, the “no” campaign managed to communicate a message of inclusion, optimism, and progress beyond violence. People likewise became convinced that their vote mattered.

When October 5, 1988, arrived, the decision was without doubt: 56 percent of voters chose to reject Pinochet and proceed with fully democratic leadership.

This moment, captured in a mix of documentary and dramatization, is particularly important because the end of the dictatorship came by democratic means. Further, it was a David and Goliath struggle, since the opposition had only 15 minutes per day for a month — nothing compared to the state’s complete control of the media.

Most Latin American countries have weak institutions, and the electoral dynamic tends to pit one populist against another as they promise more demeaning and irrelevant handouts. This campaign was distinct, since it had no visible leaders and promised just one thing: happiness. It was also respectful towards the Chilean population, didn’t attack to the regime directly, and offered a consistent message.

This film is impressive, and not only because of the script and production. It shows to both Latin America and the world that another political dynamic is possible. As citizens of each of our own respective countries, we can and should hold politicians and their campaigns to higher standards. Campaigns should be a means to understanding options in an election, and the onus is on us if we do not want to be scared into submission or misinformed.