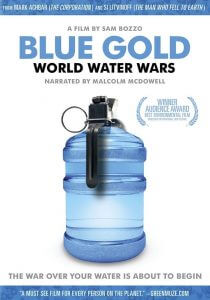

Water scarcity is and will be the source of conflicts, both national and international. As a most basic human need, individuals should pay attention to this critical topic and act on that information so we can “save ourselves.” That is the inescapable message of Blue Gold: World Water Wars (90 minutes), a 2008 documentary.

The film doesn’t hold back from appealing to one’s emotions, and zeroes in immediately on how water quality and availability can impact you personally. The viewer has already signaled his interest by proceeding beyond the title and is engaged by a call to action within a few minutes.

Blue Gold details the processes by which human activities pollute water supplies, ties these into current events, and then projects a perilous road ahead. Examples such as the disappearing Aral Sea of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and the 2000 Water War in Bolivia demonstrate what happens with poor management of natural resources. Just this month, Bolivia declared a state of emergency on account of grave water shortages, and supplies have run dry in half the nation’s municipalities.

In some ways, this film should not be necessary, since these problems are right before our eyes. We have all seen pollution in rivers, lakes, and oceans. Similarly, we have seen dry areas where water once flowed.

These problems will not solve themselves, so I am compelled to agree with the documentary: each individual should pay attention to and take action regarding the local environment, including water supplies.

Blue Gold examines two key themes, with conservation in mind: (1) the struggle for power and (2) innovation to alleviate conflicts.

The producers contend that private companies have monopolized supplies and thus increased water prices, harming the world’s most vulnerable people. They acknowledge dangers associated with state control of water, but they still characterize it as a right and want it accessible to everyone as a matter policy.

That begs the question, how can we limit centralized power and balance the state and private sectors to achieve comprehensive access to clean water?

This is where technological innovation deserves attention. Since the documentary’s production in 2008, technology has advanced tremendously, and that includes approaches to environmental protection. In particular, we need sustainable, cost-effective ways to purify water and process sewage and waste material. One of my favorite examples is LifeStraw, a Swiss-designed filter that removes 99.99 percent of bacteria and parasites. Its simple design and small size allow it to alleviate humanitarian crises.

Blue Gold producers want an end to the privatization of water supplies. Further, they call for a UN convention and accord on water access and conservation, to strong-arm nations into like-minded policies. Even if their diagnosis is legitimate, their choice of treatment places too much faith in the corrupt and unaccountable United Nations.

Their deference to the United Nations fits a demonization of private corporations throughout the film and the accusation that they have created a water cartel. This is ironic, since the producers go after Veolia, a French firm that has gone to great lengths to conserve natural resources and adhere to broader concerns of social responsibility. Veolia also sends a portion of its revenues to support local development through entrepreneurship and innovation.

The producers might like to consider my LifeStraw example. In developed countries, one can easily access this product, but it is most necessary in the Third World. Is the lack of availability the fault of the company hoarding supplies? On the contrary, the company wants to sell its product — the more the merrier. Trade barriers in the developing countries and poor economic climates keep modern innovation at arm’s length.

The unbalanced characterization of market power in Blue Gold, relative to political power, blinds the viewer to his capacity to influence and even bring down corporations. Lest we forget that they shrink or expand as a direct function of our demand for them. Likewise, if we do not like them becoming cronies, we should hold elected officials accountable and ensure open bidding and limited contracts.

The film’s key message, though, remains: we can save ourselves. In particular, when water preservation and use is our concern, we should harness the creativity of the individual. When there must be some degree of centralization, as may be the case with public water supplies, there still needs to be openness for innovation and competition of the private sector, including from abroad.

Nations that guarantee free enterprise would also alleviate water concerns through a healthy charitable sector. Consider Ryan’s Well Foundation, a Canadian nonprofit that goes to the poorest regions of the world and builds infrastructure to provide “effective and sustainable solutions to the water crisis.” The founder was a child who was surprised when his teacher told him that thousands of people were dying every day, because they did not have access to water.

He isn’t waiting around for the United Nations. No, he gets involved and saves lives, and you can too.